Publisher’s Note:

What follows is an extraordinary portrait of Frances Carroll Grevemberg, the controversial lawman, war hero, and erstwhile gubernatorial candidate whose four-year tenure as Superintendent of the Louisiana State Police under conservative Gov. Robert Kennon transformed the agency into a professional operation and marked the beginning of the end of an era for gambling racketeering.

Originally published in the Summer 1990 edition of Louisiana Trooper, a law enforcement trade publication, it is being republished, with permission, for the first time by the Bayou Brief, courtesy of its writer, Ronnie Jones, and thanks to the generosity of Doreen Wolf, who transcribed the original work.

Grevemberg, who died in 2008 at the age of 94, rarely spoke to the press following his defeat in the 1960 race for Louisiana governor, yet he remained a consequential and influential force on state politics throughout his life, often credited as a pioneer of the modern Louisiana Republican Party.

Soon after this interview first appeared, voters would overwhelmingly approve a statewide referendum to establish a lottery, something Grevemberg vigorously opposed.

When Frank Grevemberg first began his campaign against “one-armed bandits” in the 1950s, he earned the ire of mobsters and the politicians and sheriffs in the pocket of organized crime. There was a credible attempt to kidnap his twin two-and-a-half year old sons. But he never relented as a culture warrior, even though society eventually moved on.

There is one story about Grevemberg that isn’t included in this interview: He once claimed that, while he was en route to a casino bust with four long-time state troopers, he was told of a conspiracy to frame Dr. Carl Weiss for the assassination of Huey P. Long in 1935. According to Grevemberg, Long was accidentally killed by his own bodyguards after opening fire an unarmed Weiss. Troopers planted a weapon on Weiss, who lay lifeless after being shot 61 times, and colluded with the Long bodyguards to conceal the truth from the public.

Long’s biographer, T. Harry Williams, disputed the account. However, in the past three decades, Grevemberg’s version has gained significant credibility. (In my opinion, there is already sufficient evidence to disprove the notion that Weiss was responsible for the Kingfish’s death).

I should make clear that my intention here is neither to lionize nor to demonize Col. Grevemberg. Rather, it is to preserve this provocative interview with one of Louisiana’s most influential and powerful 20th century leaders for the sake of posterity.

I am currently working on a book about Carlos Marcello, and Frank Grevemberg looms large in his story as well. This is a story that needs to be told. Thank you Ronnie and Doreen for providing me with the opportunity.

All the best,

Lamar White, Jr. | Publisher, Bayou Brief.

Francis C. Grevemberg

A Legend Lost

by Ronnie Jones

Francis C. Grevemberg served as Superintendent of the Louisiana State Police from 1952-1956, under Governor Robert Kennon. Most political observers contend that Louisiana wasn’t really ready for reform even though a “reform minded” governor had been elected. If that is true, then most of the state’s residents were even less ready for Colonel Grevemberg.

Most people remember Grevemberg as a crusader of sorts, cutting a swath through the political corruption which protected the social sins of the day. He took on slot machines and gamblers, prostitutes and bootleg stills, all with equal enthusiasm, impervious to the criticism he engendered. In the process a struggling State Police matured from adolescence into adulthood.

Grevemberg had grown up in southern Louisiana with family roots in New Orleans and St. Mary Parish. He attended Catholic schools in New Orleans and enlisted in the National Guard when he was 18. By the time the second World War had broken out he was a second lieutenant in an Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion.

His military training and experience would have significant influence on how he deployed his troopers in the years to come. There was plenty of experience from which to draw. He was trained by General George Patton and he served under the son of Teddy Roosevelt. His unit plodded through North Africa, Sicily, Anzio and the south of France. He watched, arm’s length from General Bradly, as the allied invasion was launched.

Promotions followed one after the other. At 29 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. Through nine campaigns, the Military Valor Cross, the Legion of Merit for Combat and the Soldiers Medal for Heroism, Grevemberg did what good soldiers are supposed to do — he followed orders, learned the necessity for discipline and took pride in himself. And as an officer he did what good officers were supposed to do — he led others into adversity, he planned strategy, and he commanded respect. They were attributes which would serve him well in future endeavors.

When the war had finally ended, he returned home to face new challenges. What had not changed in his absence was the temperament of Louisiana politics.

The year was 1951. It was November and that meant election time in the Bayou State. Life magazine saw it this way:

Through the length and breadth of Louisiana last week rolled the biggest road show the land of the Kingfish had ever seen. The high white capitol the late Huey Long had built in the days of his pride would soon have a vacant office — the term of Governor Earl Long, Huey’s brother, was due to expire. By law Earl could not succeed himself and there were 11 candidates out after his job. In the back hills and bayous, through the tiniest towns and the cities, their sound trucks leapfrogged ahead of one another to drum up crowds for speeches. And candidates were finding it necessary to bellow promises as often as 15 times a day. Even for Louisiana it was a political madhouse.

Earl Long wasn’t about to be left out of the politics just because of a little old Constitutional prohibition regulating succession. He “sponsored” a candidate, Judge Carlos G. Spaht. But Uncle Earl’s ticket, however, was rejected, and from a field of candidates which included a black and a female, Robert Kennon emerged as the winner with a grand plan for reform.

Indeed, there was much which needed “reforming.” The state had serious problems, not the least of which was its national image.

Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver had been ferreting out witnesses around the country to talk about the national menaces of gambling and organized crime. Louisiana figured prominently into those hearings. (Wouldn’t you have figured that?)

It was reported that our state had its share of gambling problems and that they were likely well organized. The tentacles of mobsters Frank Costello and Dandy Phil Kastel had reached well into all corners of Louisiana.

One report compared New Orleans to Caeser’s Gaul; it was divided into three equal parts. In this case Caeser held dominion over St. Bernard, Jefferson and Orleans, each parish with its own organization and benefactors. Another report indicated Louisiana had a thousand more slot machines (where they were illegal) than Las Vegas.

Jefferson Parish’s Sheriff Frank Clancy, who testified before the committee, assured the well-intentioned Senator there might be some little pockets of low stakes games here and there, but no real problems. Clancy brought an almost circus atmosphere to the otherwise staid proceedings.

When Kennon was inaugurated, he probably had no idea his recently appointed superintendent of State Police was already making waves. When he took the helm of State Police it was listing badly and foundering in a sea of politics.

Grevemberg has been variously described as intractable and unequivocal, youthful, dedicated and humorous. One reporter who has chronicled Louisiana politicians and politics for years called him the “most honest man he had ever met… a man perhaps ahead of his time for Louisiana.” If honesty and integrity were the qualities Kennon’s men sought in appointing Grevemberg, then they probably got more than they bargained for.

A lawman of the purest order, Grevemberg was often quoted as saying that he got paid to enforce the law, and that’s precisely what he did. Some observers would say he saw things only in black and white, right and wrong, legal and illegal. He doesn’t really deny that characterization. In his own mind he found little if any room for negotiation between the extremes.

Ed Tunstall is a former editor and reporter for the New Orleans Times Picayune. He recalls Grevemberg “had a presence, a presence of law and order. He was a man who was matter of fact. With him, there were no ifs, ands or buts.”

And nationally syndicated Associated Press reporter Hugh Mulligan also covered Grevemberg’s tenure in office. Aside from the many stories of the colonel’s adventures through Louisiana’s corrupted government, Hugh admired what was done to State Police in the process.

Hugh believes that in the wake of Grevemberg’s four-year appointment, he left behind a better organization, one with high morale and one more effective at achieving its law

Grevemberg spent the better part of an afternoon with me recently. We visited in his home in New Orleans where he lives with his wife of 53 years. We sat in his studio surrounded by his paintings which hang on the wall. An unfinished piece of sculpture was in one corner. Exercise equipment was jammed into every spare piece of floor space.

The window-unit air conditioner droned on endlessly and made it difficult to hear when his voice trailed off. At 76 years of age he looks amazingly well and fit. Only in the last few months have the years begun to take their toll. He moves slowly now; rheumatoid arthritis has temporarily swollen his joints. The pain and inconvenience which results frustrates him.

But his mind is as clear as a spring morning. For the first time since leaving state service he talked candidly about his career, the highs and lows, about his ill-fated decision to run for governor, and the forces which drove him during those four years as superintendent. For those of you who don’t know Francis C. Grevemberg, let’s meet him.

What preceded your appointment to Superintendent of State Police? Tell us how your appointment came about.

When I returned from the war I went to work selling real estate in New Orleans. For a number of reasons, I got out of that business. Looking back, that was probably a mistake. A hotel property became available over on the Gulf coast and I went in on it with a family friend of mine. We purchased the hotel on my 34th birthday. But wouldn’t you know it, on the day we purchased it, the bridge burned down, that is the bridge going across Bay St. Louis. It was an all wooden structure and it burned. That left no convenient way for people to get from the city (New Orleans) to the coast. The hotel was booked for the summer mostly with Orleanians. We lost money and just did not have the capital to keep going. Twelve months later we sold it to an attorney from Chicago, thank goodness.

We could have lost everything we had at the time, but we didn’t. We (my wife and I) returned to New Orleans and bought a new house and a new car and even had a little cash left over. I was selling stocks and bonds and some real estate on the side when Colonel Wilburn Lunn asked me if I wanted to work for Governor Kennon (in a political capacity during the campaign). Wilburn was an ex-Army colonel with whom I had served while in the south of France. After the election he would later serve as the executive counsel to the governor. At this time he was Kennon’s campaign manager, and I told him that I didn’t know a thing about politics, but Lunn was determined. He told me that if I could help get 25,000 votes out of New Orleans we could win the election. I told him l would help.

I didn’t appear on television, there wasn’t much TV anyway, and I didn’t make personal appearances on behalf of Kennon, I didn’t stump for him. I worked behind the scenes.

After Kennon was elected, I didn’t even personally know Kennon, Colonel Lunn contacted me again. He said, “Grevy, this is Wilburn.” I said. “Yes, I recognize your voice just by saying Grevy.” He asked if I would like to be Adjutant General? l said, Adjutant General? Jesus, I was commander of the 204th Aircraft Artillery Group in the National Guard and had been made a full colonel in June of 1951, but Adjutant General. I just couldn’t believe it.

In the fall, prior to the election, an article appeared across the state which called my unit the most combat ready unit around. When we had gone to summer camp, we broke all records. The unit was judged by regular army people and our unit was judged to be exemplary.

So, Lunn had seen this article and my picture which had appeared together with the article, and he figured, who better to serve as Louisiana’s Adjutant General. He said, ”I saw the article about your group in the paper. I was with you (during the war) and I know the job you did with us. And I know you can do this.”

I gave the offer careful thought. One problem was the AG I was replacing was a personal friend of mine, but we worked that problem out and I told Wilburn I would take the position.

About two weeks later I severed my relations with my two jobs so that I could have a little time to rest before taking the new position. I was 37 at the time. Almost as soon as I had severed my ties to my jobs Wilburn called and said, “I’m sorry but I can’t give you the job as Adjutant General. When I told the Governor, it seems that he had already promised that job to another General who was working in Washington over all the National Guards in the country at the time. Kennon simply forgot and he is very sorry.”

“Sorry?” I said, I can understand the problem, but now I don’t have a job. I was very disappointed. But Wilburn went on. “I’ve got something else right down your alley.” I said, what’s that? And he said, “Stace Police. How would you like to head up the State Police?”

I said, no, l don’t know anything about police work. I don’t even like to watch it on TV. It’s much too violent and I’ve had enough violence in my life. He said, “bull …., come on up here (to Baton Rouge) and talk to me. Let’s talk about it and I’ll show you what you are getting into.

I agreed and made arrangements to visit Colonel Lunn in Baton Rouge. I intended to visit the organization and look things over before I consented to take this job.

What did you find when you came to Baton Rouge?

Colonel Roy was called by Kennon’s people and told his replacement would be visiting soon to look things over. Roy had been a big supporter of Spaht who’d lost the election of course.

1 arrived in Baton Rouge and found headquarters. 1 went in there, and introduced myself to Colonel Roy and told him 1 had come up to visit the facility and talk to the troopers. He said, “my God, how old are you son?” And I said 37. He started laughing and I just mentally filed that away.

Troop A was right on the compound, so he took me in and introduced me to Captain Walker. Martin Fritcher and Lonnie Rogers were there along with several others including Ben Ragusa. I talked with them and everything seemed alright. Then he walked me all the way through to the Identification Bureau where most people worked.

About that time Col. Roy said, “well, I think we’ve been here long enough sonny boy; we need to wrap up.” And I said, “look, I’m ready anytime you are old man,” because he was about 65. So, I didn’t have to listen to that “sonny boy” stuff anymore when we went to other sections .

I told Wilburn that I wanted to visit the troops in the field as well so he set me up an itinerary and directed all the troopers to be present when I made my visits. I started out in Baton Rouge then went to Alexandria, Monroe, Shreveport, Leesville, Opelousas, Lafayette, New Iberia and finally New Orleans.

Had you officially accepted the position yet?

No. I wanted to look things over before accepting.

What was your overall impression after completing your tour?

I wasn’t impressed. I didn’t like the way things looked at all. When I returned to Baton Rouge, I reported to Colonel Lunn that it was the most pathetic looking outfit I had ever seen. I said it was obvious that some of these men are farmers, and they had been plowing their fields in their hats. All I had to do was look at their hats, they were full of perspiration and filthy. I told him that some of the men looked like they hadn’t shaved in two or three days. Their uniforms were not clean; their pants were dirty, and it looked as if most men had never even fired their revolvers. Things were obviously in pitiful shape.

I told Wilburn that I’d take the job despite the problems but that I’d need an assistant, someone with a military background. He agreed. It was a challenge and I wasn’t afraid of a challenge. But I told Colonel Lunn that I wanted to be independent, I did not want to have to work for Chester Owens who had been appointed Director of Public Safety. l wanted a free hand to run State Police. Governor Kennon had promised the people good, clean, “civics-book” type government and I could not do my part if l had to report through a political deadhead in charge of Public Safety.

I didn’t, by the way, promise that I’d do anything about gambling during my conversations with Colonel Wilburn. In fact, to me that issue was, or at least should have been understood. After all, how could you hope to have good, clean, civics-book type government when illegal gambling was corrupting all the politicians throughout the state?

Did Colonel Lunn give you that promise?

He did. He told Chester that he’d be doing a lot of fishing and told me that I’d be running the entire department. But I told him that l didn’t want the whole department, that would make Chester a real deadhead and we didn’t need any more deadheads. So, we let him run the driver’s license division.

How politicized had the department’s administration become when you took over?

It was strictly political. Every time there was a change in superintendents, the new one would fire everybody who they even suspected had worked for the opposing candidate. I also understand that in other administrations, for example, if State Police wanted to conduct a gambling raid, the superintendent had to call the owner and tell him that a raid was going to be made. The owner would then arrange for several patrons to be present so arrests could be made. And of course, it was widely rumored, and likely true, that the raiding party was pocketing the evidence.

Chester Owens was related to Sheriff Owens in Sabine Parish and there were all kinds of allegations by people from that area about corrupt politicians. Some said that gambling was rampant. I don’t have personal knowledge of such activity in that area but I do know Mr. Owens wanted me to fire Wingate White who was my troop commander there.

I simply told Chester that I was not going to fire someone because the trooper wasn’t popular with the local politicians. I intended to bring Civil Service protection to the troopers, which I did, and such firings were not consistent with the way that I operated. I eventually brought Wingate down to Baton Rouge and used him on special assignments, investigating gambling and such.

The entire operation of State Police had suffered over the years. There was no crime lab capability for developing or examining evidence for example. Everything had to be sent to Washington to the FBI for examination. That was one of the things 1 wanted Colonel Lunn’s assurances on, that he would help us get the money necessary to do what had to be done. I didn’t want the old-time politics to get in the way of doing what was right for the troopers.

I officially took office on May 13, 1952 and moved into the old white wooden house in which Internal Affairs is currently located. Chester moved into the brick house before I could and I probably could have had him moved out but 1 didn’t. Dorothy, my wife, did not move up to Baton Rouge until September of 1952 — after the kidnapping of our twins – but I’ll get to that.

What were your first priorities after assuming office?

The main thing I wanted to do was increase the salaries of the men. They made $175 a month. I could not figure out how I was going to increase it because l needed several million dollars to do so, but this was my number one priority. I knew that I could not get good solid men for that salary. I had a lot of people I should have fired which would have permitted me to hire some new qualified men, and I probably made a mistake by not firing them. But I didn’t.

My second priority was organization and development of a crime lab. And I suppose my third priority was placement of troopers under Civil Service protection.

What was one of the first positive things you did when you initially took over?

I hired Aaron Edgecombe and made him a major, he was the only outsider I hired. He was a military man, who was my First Sergeant of my training battalion, a man that l knew was a real disciplinarian. The troopers despised him. But this guy did exactly the job I wanted him to do. This guy made the men look sharp. The appearance changed almost overnight. They were required to shave every day, wear clean uniforms.

l also wanted to get started on the Civil Service effort right away too. l worked my tail off getting us into Civil Service and so did the troopers. I told all the troopers to go out and work the legislators, to get support for our effort. That was only one of two times that l had the troopers work their legislators to get something accomplished.

What kind of relationship did you have with the governor? How would you characterize the formative days of your administration?

I was in office the first day and had not even met the Governor yet. A reporter from the Times Picayune, Ken Gorman came by about 2:00 in the afternoon. He wanted to see me and he introduced himself. He asked to see the file on the State Police Benefit Fund. I told him that I wasn’t familiar with the fund but would find out about it.

I called around the compound and asked several officers about the fund and everyone told me that they weren’t familiar with the program. The Assistant Superintendent also denied knowing where such a file was.

The reporter knew better, and so did I. Gorman told me that my predecessor, Colonel Roy, had admitted to the existence of the fund and had actually had the file on his desk during the previous interview. I called our auditor at the time, Captain Neeson, and told him, “Captain, I can understand why you might want to be protecting the Assistant Superintendent, but I know the file exists and I want to see it right away.”

The file was brought in and 1 had never seen it. To my surprise and that of the reporter, when we opened it we saw that a check had been made out to the “Carlos Spaht Campaign Fund” for $12,500. The check had been signed by Colonel Roy who also served as administrator of the fund. It was countersigned by the Assistant Superintendent who served as Vice President of the fund.

Can you imagine how surprised I was. Here was a fund into which every trooper on the force was contributing 50 cents per pay check for flowers, funerals and other special trooper needs being blatantly used for politics.

Well, the reporter compiled quite a story. It was on the first page of the Picayune, a picture of the check was blown up right there on the front page. Roy was denying the whole thing of course. But we called in everybody who had known about the contribution or served as a trustee and asked them about the fund. They all insisted that Roy had coerced them into agreeing to the contribution.

That night at the Inaugural Ball in the receiving line, Dorothy and I were introduced to Kennon for the first time. Kennon introduced me as his new Superintendent of the State Police. I was already in office, had uncovered significant apparent corruption, caused some waves and he didn’t even know about it. I’m sure he was shaken by the front page of the paper the next day, no one in his administration was involved, so everything was O.K.

How did the gambling issue take off? What were your first indications that gambling was going to be such a sensitive and important issue to you and the State Police?

On the fifth day after taking over, James McLain, an Associated Press reporter came into my office. He brought a number of documents and photographs with him alleging that gambling was widespread.

He told me he had already been to visit then-Jefferson Parish Sheriff Frank “King” Clancy and Clancy had denied any serious gambling was going on in his parish. The Sheriff characterized any gambling that might be going on as minor and small mom-, and pop-type operations which were hurting no one. Moreover, the sheriff did not intend to do anything about such games.

The reporter said he had also confronted Sheriff Rowley in St. Bernard Parish and the Chief of Police in New Orleans with similar evidence. Both officials denied gambling was a problem in their respective jurisdictions. McLain quoted the New Orleans chief as saying that insofar as gambling was concerned in his city, “Not a thing going on; it’s as dead as it can be, If you don’t believe me go ask the cab drivers.”

McLain did just that. He went over to the Roosevelt Hotel and asked the drivers where he could find some action. The driver replied first with a question, “You mean gambling?” Then he told McLain what he was looking for. Gambling, it seemed was readily available — there are about eight casinos open in Jefferson and several open in St. Bernard, quite a few in New Orleans. And lotteries, there are two operating

in New Orleans. There’s eight of them in the area. There are handbooks everywhere too.

McLain told me that on the way up from New Orleans he stopped off in St. Charles Parish at the Bar None Ranch and it was running full blast. He had also stopped off at the College Inn located in LaPlace. There he found two dice tables, a roulette wheel, black jack tables and about 200 customers.

Across the river from Baton Rouge the same night he found gamblers were as thick as thieves. When asked, the local sheriff denied that there was any gambling going on.

So here this reporter comes, into my office, I’ve been there less than a week and he lays out all this evidence of illegal gambling. And he asks me, “Colonel, what are you going to do?” I told him that l trusted him and that I believed what he had brought to me.

I gave him a statement that established my posture on gambling. l issued an order stating that gambling was illegal. I quoted the Revised Statute 14:90 that gambling is evil and that the Legislature is obliged to enforce it. The slot machines were to be considered contraband. The State Police has an obligation to enforce state laws within the entire confines of the State of Louisiana.

1 told him that local officials did not have the right to lessen the effects of the state law. I gave McLain the statement in hopes that the local sheriffs and police chiefs will abide by it. I said, “Effectively immediately, illegal gambling in Louisiana would not be tolerated unless the Legislature changed the law.” But I knew that the law could not be changed without amending the State Constitution.

So, I said there would be no more gambling and if the enforcement officers locally wouldn’t enforce the law the State Police would enforce it for them. l said l don’t know how plainer I can be than that. We have a job to do and I am bound to do it, to enforce the laws of the State of Louisiana. He thanked me and left.

How was the news received?

The news hit the headlines the next morning, all over the state, not just in New Orleans, but in every little paper and every big one. The article outlined how the activities in several “dirty” parishes were “slopping over” into parishes where there was no gambling, and it named parishes. By the time I got into the office the next morning the phone was ringing off the hook. Sheriff Clancy was one of the first I talked to.

Clancy told me, “I’m not going to disagree with your article, but I object to the phraseology.” l asked him what he meant. He said, “Well when you said when a dirty parish like Jefferson slops over into a clean parish like Orleans, it’s not true. The truth of the matter is, the dirty parish is Orleans and it’s slopping over into Jefferson. If you’ll check you’ll find that little self-styled saint (the mayor of New Orleans) polishing his halo all the time is a hypocrite.” To make his point, Clancy gave me a list of 12 addresses in the city where gambling was being conducted.

Calls from two other sheriffs followed with the same complaint. Ironically, both provided lists of gambling houses in New Orleans — the same 12 which had been produced by Clancy. So, I picked up the phone and called the mayor in New Orleans and related my conversations with the sheriffs. I told him that I didn’t want to just run into the city and subvert his authority. l considered the call a friendly warning. I gave him two weeks to straighten out the problem. I really didn’t want to go sneaking around in someone else’s area.

That night the city police raided six locations and the Picayune covered the story. The six locations were six of the twelve I had provided, so everybody knew the raids were motivated by me.

Did that signal a spirit of cooperation between you and city officials in New Orleans?

Absolutely not. I had more trouble with them than anybody else. The city had a large delegation in the legislature and the governor needed the votes for his programs. I caused some real problems.

Every time the Legislature would meet I would get a call from Colonel Lunn; the Governor wouldn’t call me himself. He would say, “You know you’re messing up the governor’s programs, why don’t you take a vacation.” He would laugh because he knew I couldn’t do that, but he had to ask.

What other reaction was there to your hard-line position on gambling?

The day after the article ran, my secretary told me there were five men outside waiting to see me. One of them said he was Governor Kennon’s State Campaign Finance Chairman.

So this little cocky man strolls in and says “I’m so and so, I was Governor Kennon’s State Campaign Finance Chairman. I want you to sit behind that desk and call the reporter who wrote that article about gambling. And I want you to countermand that information about gambling.”

I asked if that was an order and he told me that it was. But he was surprised when I told him, “I’ve got a big secret for you; l don’t take orders from you. You tell the governor that if that’s what he wants me to do, that I’ll go back to New Orleans and tell the whole story. The headlines will be as big as the paper is long. I’d tell the whole story; I’d be forced to resign and I’d tell everything.” I told him that you couldn’t have good government with gambling running in almost every parish in the state, and the public officials were taking bribes to permit it.

The cocky guy told me I didn’t understand — he pointed to each of the men who’d accompanied him. This guy gave the campaign $300,000 on behalf of his club, this guy gave $25,000. This guy gave $450,000. He continued around the room until I stopped him. I told him it wasn’t a matter of money, there wasn’t going to be any more gambling as long as I was superintendent.

I suppose they saw that I wasn’t going to budge so they dropped it. But before leaving they asked for badges, badges that said Special Agent or Investigator. I asked why they needed badges and they said when they get stopped by a trooper they wanted to be able to pull the badge to show that they were a trooper and not get a ticket.

I told the fella’ that I wasn’t sure what he was asking for but I would look into it and if the law permitted him to be issued a badge, I would get it for him. But of course, the law didn’t. The gentleman stormed out of the office after calling me a son-of-a-bitch. and telling the others that I was crazy.

Very shortly thereafter, I heard from the Governor. He told me, “You know you took a very big step this morning.” I said, “yes it was and it must have been a big step for you too, Governor.” And he said that it was indeed.

What else did the governor have to say about the controversy you had stirred?

Well, he told me, “Colonel, you know those slot machines are quasi-legal. The state requires the purchase of a $100 stamp for each machine and the stamp is valid for one year. Now we just can’t go in and confiscate all those slots, call them illegal and take them out and destroy them. The owners have already paid for their use.”

I told the governor that stamp didn’t mean a thing, in fact there wasn’t even a stamp on most machines, they had just paid the $100. I asked him, when is the year up, when does the so-called stamp expire? He didn’t know. But more importantly, he didn’t tell me not to remove the machines when the stamp expired. So, I figured that when the expiration rolled around, I’d just go around and pick up all the machines. He hadn’t told me I couldn’t. Then he could blame the whole mess on me. Basically that’s what I ended up doing.

I don’t think anybody was surprised to find out that about 4,000 machines were properly stamped; we eventually destroyed over 8,000.

My main problem was that the governor wanted me to contact the media and tell everybody that the slots were legal and that they would not be seized. Of course, there was the possibility that my credibility on the whole issue would be adversely affected so I told McLain (the AP reporter) the entire story in confidence. What I said for the record was that the Attorney General had ruled that the slots were quasi-legal until the so-called stamp expired. We wouldn’t be confiscating any slots until then.

When the story finally ran, all hell broke loose. It looked to everybody like l was going to back off the whole gambling issue. People from all over the state were calling and I didn’t have any PR man to handle the media.

The Advocate in Baton Rouge ran an editorial, it was at least a half page. lt said something like, “We have the fastest dealer ever in charge of State Police.” They took the opportunity, on what they believed to be my changing positions on gambling, to criticize me. It was really unfair and I told myself, okay, I’ll make them eat those words. I eventually did too.

The press just did not believe you meant business in other words?

That’s right. They just figured that I’d come out strong against gambling and backed off like everyone else had. But I had news for them . So I planned some raids to let people know I meant business.

Tell us about some of your first raids.

One of the first attempts was the Bar None Ranch which was owned by Add Given Davis.

Where was that?

What happened?

I called six troopers, brought them into my office and briefed them on the pending raid. Major Edgecombe had already gone in and looked things over for us. I just picked six officers, didn’t pay particular attention to who they were, I just picked them.

Anyway, we drove down there, we all go in sort of a convoy. Edgecombe goes with me and we pull up in front of the curb and guess what, there’s not a car in the parking lot. Deserted as it can be. The place was closed. So, it was obvious some of my own guys tipped off the folks there. But I learned a lesson.

How did the next one go?

Well, the next night I picked out some men and didn’t tell them where we were going. I simply told them to follow me in their vehicles. I told them if they had to go to the bathroom they better go before we left. There would be no stopping the vehicles once we left, for any reason, not to get gas, nothing. If they tried anything funny, I’d fire every one of them, that was before Civil Service of course.

We pulled up in front of the College Inn in LaPlace, I ran up to the door and kicked it in. Nobody had a chance. There were something like 200 people in there and just the seven or so of us, and God there was money everywhere.

I remember there was this one little guy in there with suspenders and seersucker pants. He was playing with silver dollars rather than chips. When we came in, he started stuffing dollars in his pants and his suspenders kept getting longer and his pants lower and lower to the ground. We didn’t have time to fool with him, but he was a sight to behold.

As we walked out after making the arrests and everything, all the patrons sort of lined up and began to shout, “Heil Hitler, Heil Kennon, Heil Grevemberg.” But they didn’t spit on us though, that happened later.

Did the press respond positively? Were they convinced that you meant business?

The papers picked up on it immediately and it was reported everywhere. They were really watching me closely to see if I was going to continue the raids. That weekend, and this is still my first official week as superintendent, when I returned to New Orleans, I drove by the Top Hat Club which was at that time near North Broad and St. Ann. I rode by, it was a real big place, like a big garage with two big doors in front.

I looked in and saw all these people playing Keno, roulette, throwing dice, sitting at blackjack tables and so forth. I called for some troopers and six came over. This was on a Friday night. We arrested about six of the operators, the ones who seemed to be running the games, but we didn’t arrest those just playing.

Now the Club is in the city limits you understand and it was one of those clubs which I had brought to the attention of Chep Morrison (deLesseps Story Morrison, the New Orleans mayor) and the chief in New Orleans. But of the six places which the City Police raided, this wasn’t one of them.

So when we took the folks who had been arrested down to the first precinct on Rampart I could hear some of the local officers talking under their breath, things like, “that son of a b …. , who does he think he is? He’s cutting off our gravy train,” and stuff like that. Some were more blatant than others.

I knew I was going into an enemy camp. We walked on and in and were booking the prisoners when one of the local officers came over and introduced himself as Bill Pettingill. He asked if I knew his brother who was a prize fighter and I told him that I had followed his career because I used to box myself. And he went on to tell me that he was half owner of the club we raided with his brother.

Didn’t he attempt to bribe you?

Yes, eventually. He told me, “You really tore your drawers down there by pulling that raid.” He knew by my look I didn’t understand what he meant. He told me that there was a sign on the wall declaring that the games were for charity and that the proceeds above the costs of operations went to the little Sisters of the Poor.

I said boloney! That sign doesn’t mean a thing. I told him that even charitable gambling is not legal, cakewalks, raffles, none of that stuff is legal, particularly a casino. In fact, I had checked with the little Sisters of Poor and they weren’t getting anywhere near what was being taken in by the games.

I went down to the District Attorney’s office the following Monday about this case and Pettingill approached me. He apologized for his comments at the precinct and asked what I wanted, drugs, cash, women. He told me he could get me the hottest gals I’d ever seen and they’d do everything I wanted. I told him that I didn’t want anything but my salary and I had him booked for bribery and running a gambling house.

But the DA never did anything. The phony trial didn’t even make the paper because the reporters I knew weren’t there. The officer was put back on the force with full pay and benefits. Can you believe that?

How frustrated did Chep Morrison get with your raids in the city?

Chep was frustrated. He kept complaining to the Governor and Colonel Lunn. The mayor kept telling them that I was wrong. He was telling reporters that l was sneaking around behind his back because I was going to run for political office in New Orleans. He was full of bull. Although I did run for state office later that had nothing to do with my raids.

Anyway, with all his complaining, we sort of reached an agreement, but it never worked.

What proved to be the most difficult raid you had to pull in the city?

The City Police had been trying to get into the 123 Club at 123 University Place right across from the Roosevelt for years. It was run by associates of the Costello-Kastel mob. New Orleans’ Chief Scheuering either had been ignoring the dice and roulette club or had just been unable to get inside. Because of the layout and screening of patrons it was a tough place to get into.

I went down to check things out personally. I wore glasses and a fake mustache. I sat down at the bar and had a couple of drinks . I studied the layout. There was this little iron stairway going up to the mezzanine where there were some more cocktail tables. So I went up there and ordered a drink.

When I got up there I saw a door. People were going in and out of it. l also noticed that when anybody came up the stairs and the bartender was obviously ringing some kind of bell to alert an attendant upstairs. Inside the door of the 3rd floor is where the gambling was going on, and the bartender seemed to be the link in getting people in.

I knew I had to try and use somebody to get inside who would be accepted as a gambler. So I scoured our personnel files and found this trooper from Lake Charles who’d worked in a gambling house years earlier. We had him apply for a job and the operators hired him.

He was placed in a hotel lobby as “hustler” to bring in prospective gamblers who might be staying at the hotel. Then we sent in a couple of other troopers. They drove up in front of the hotel in a big Cadillac and were tipping big. Every hustler in the lobby moved in on the two troopers disguised as businessmen. “Our hustler” was obviously the one they went with.

They were escorted to the lounge and headed upstairs. They walked past the lookout men and waltzed right into the gambling room. At precisely the same moment, Major Edgecombe and I converged with other troopers on the lounge.

They never knew what had hit them. Our raid was timed down to the second. We had paced our steps to the front door.

You’ve mentioned the Mafia connection, you were obviously playing in the major leagues. What kind of response did your raids bring?

It wasn’t long after that that the heat really got turned up. Sheriff Clancy from Jefferson called me and warned me, “If you don’t stop the raids in New Orleans, St. Bernard and Jefferson, I hate to tell you what’s going to happen to you. Because the guys you’re playing with are playing for all the marbles. You’re gonna’ end up a dead woodpecker. I just wanted to warn you.”

I said well I don’t know what a dead woodpecker looks like but I have an idea, thanks.

How seriously did you take the threat that Clancy passed along?

Well, l took it seriously because he made the effort to pass it along. l wasn’t as much concerned about my safety as l was Dorothy and the twins. They still lived in New Orleans at this time.

When was the kidnapping attempt made on the kids?

They didn’t come to Baton Rouge until September. l had received all kinds of threats. They had threatened to kill my kids and they had threatened to kill Dorothy too. They sent me a “blackhand” letter that I turned over to the FBI and they confirmed that it appeared to be legitimate.

Anyway, at the time I had a house in Lakeview. One evening Dorothy was alone at home with the twins, they were about two-and-a-half. She was reading downstairs while the kids slept upstairs.

We had this small screen porch which ran along the side of the house, and one could gain entrance to the upstairs by climbing onto the porch roof and climbing in a second-floor window. Well, that’s just what two guys tried to do. When Dorothy heard noises from upstairs she got up and shut the downstairs door and headed up the stairs. That apparently frightened whoever had climbed in because they got out fast. As they left Dorothy heard what she thought was the crackle of a radio, like a police radio or something. Of course we’ll never really know who it was.

Our neighbor happened to see the men climbing onto the porch and by the time he tried to warn Dorothy the intruders were apparently frightened away. So his warning came too late, but it did confirm that someone definitely got into the house. The FBI also confirmed that it was a kidnapping attempt.

l had everybody moved up to Baton Rouge with me right after that. But I wasn’t going to be bullied by anybody into slowing things down. I didn’t care who was involved.

Then you took the mafia connection seriously? Give us an example of where you found evidence of organized crime.

Clancy told me that a man named Joe Peretti was very high up in organized crime and had run a wire service in St. Bernard but had moved it to New Orleans. In fact, he gave me the address. Clancy told me that Peretti was covering the entire Southwest United States and he had about twenty-five telephones in his place. I had Edgecombe check and sure enough he was at the address, there were telephone wires galore running into that little cottage. We raided him 5 times and each time he was released.

We did tell the telephone company that they were contributing to an operation of a wire service and told them to discontinue service at the address. They refused to comply and we returned later with 16-pound mauls and broke up the phones the next time. In fact, we returned and did that several times as I recall.

About four months later we heard that Peretti’s wire service was established at another location. We found him out in Arabi (a suburb of New Orleans). Peretti had bought a five-acre tract of land and had put an eight-foot edge fence all around the property. A padlock was on the gate, the fence was topped with barbed wire and there were two police dogs patrolling the perimeter. Major Edgecombe had checked the whole thing out for me.

What was your plan?

1 asked Edgecombe if he had checked the sex of the dogs and he told me that he hadn’t. As it turned out they were males. So, 1 told him to find a bitch in heat and meet me at the location. l brought a ladder and some old army blankets. We threw the blankets over the barbed wire, distracted the dogs, and damned near broke our ankles jumping over the fence.

Nobody was around. The place was deserted. Joe Peretti couldn’t believe it. He said, “you no good son of a bitch.” l think we put them out of business. I know they moved to another state anyway.

How much influence do you think Costello had in Louisiana at the time?

I think Costello still owned the bulk of the slot machines in the state. He owned every one of those slots found in the casinos.

I just have to ask, where were the feds all this time?

The federal officials had no authority to enforce any of our state laws. Just like we had no authority in State Police to enforce city ordinances.

But the feds were involved in certain areas. Federal stamps were required for some activities like slot machines and pinball machines. And of course, we got lots of help from the feds when we went after bootleggers in North Louisiana.

They worked with us in carrying out a series of simultaneous raids in the northern part of the state on bootleggers one weekend when LSU was playing Arkansas in Shreveport Everybody was so caught up in the football festivities that it left easy pickings for us. Ordinarily raids like that were usually hard to pull off because the bootleggers were protected by local politicians.

We made something like 26 arrests including the mayor of Minden and found evidence of payments to deputies and state revenue officials.

And there is another particular case which comes to mind in which the federal authorities were very helpful. There was a house of prostitution in St. John Parish on U.S. 51 between LaPlace and Ponchatoula, called the 4 Leaf Clover Club.

lt was a shotgun building and as we later found out the most unsanitary place in the state. The people would sit on the porch railing and defecate into the swamp; there was no bathroom. It wasn’t just unsightly, it was disgusting; the women simply threw their sanitary napkins into the trees out back. It was a real sight, I’ll tell you.

The building was partially on the highway right of way and the other part in the swamp on property owned by a box company. When we raided it the first time we found six prostitutes and about 25 men on the premises. We scared the hell out of the men because even though we did not arrest them we lined them up and took their names, addresses and drivers license numbers. We told them not to come back. Most of the men were married and one of them was 72.

We went back about six times and in each case we’d barely get things shut down when the place was back in business. I was getting frustrated.

How did you finally put them out of business?

Well, I got a collect call from a young woman one afternoon. She said that she was in a phone booth in LaPlace. She had been working at the club each time I had raided it. I asked her what happened to the charges and she told me that they were released as soon as the troopers left the courthouse. The charges were always dismissed.

She told me that she was dressed in a negligee, that she had heard a truck driver coming down the highway when she was back at the club and ran outside to stop him. She traded sex for a ride to LaPlace.

She told me that she wanted to be picked up by a trooper and brought to Baton Rouge. She was willing to tell me the whole story about how the girls were brought into the ring. She said that they were forced into prostitution and were never paid any money. They were given drugs for their activities. I knew that if what she was telling me was the truth, we had more than a simple house of prostitution ring, we had a white slavery case.

So 1 contacted the truck scales facility down there (troopers manned the scales) and told two troopers to go pick the young lady up, and 1 warned them not to touch her, not to get involved with her. Both of the officers were married 1 made sure of that. In advance of her arrival I called the young lady’s father and asked him to come over to my office. When he arrived related what I had been told and he did not believe me. In fact he said if what I told him wasn’t true he’d kill me.

When the young woman came into my office the father recognized her almost immediately. Her brunette hair had been dyed blonde. Well, the father just broke down and cried. Based on what she told us and with the help of the federal authorities, we broke up an eight-state white slavery racket.

Eventually we got permission from the owners of the property to destroy the building which had been built on it. We brought in a dozer and leveled the property.

How prevalent was prostitution elsewhere?

Things never seemed quite that organized in New Orleans. The places there were very discrete and select in terms of who was admitted. We just were not successful in getting any of our men into the establishments, but we knew that some were operating.

There were others throughout the state too. I recall J. Edgar Hoover had called on an unrelated matter to congratulate me on one of our missions and he asked if he could do anything for us. I told him, as a matter of fact there was. 1 told him I needed 23 agents to assist us in conducting some prostitution raids and he was good to his word.

We met in Baton Rouge and my men and the federal authorities fanned out up and down the river (the Mississippi) and conducted 23 separate simultaneous raids. We didn’t hit a dry well as far as prostitution is concerned. The FBI men were able to talk to the girls privately and they uncovered plenty of information about the extensiveness of the white slavery trade. It benefited them tremendously in their national efforts.

Did you find that local officials were protecting these operations?

Why yes. In fact one of the places we raided was Margaret’s Place. It operated right across the street from the biggest Catholic Church in Opelousas. It had operated there for 47 years without interruption. Tom Burbank led that raid, and when Margaret was brought to the courthouse, Sheriff Cat Doucet almost knocked Burbank down trying to help Margaret out of the vehicle. Doucet told Burbank, “You can’t do this (the arrest of Margaret) to me.” And Burbank asked why. “Because she gives me $300 a week in cash that’s why.”

Why did you consider it so important to suppress gambling? Was it because you did not like it personally, were you a moralist?

What was it?

Because of everything it attracts . I’m not a moralist in fact I’m not against gambling if it’s fairly conducted.

Can you be more specific?

Well, the main thing it does, is that it corrupts officials. Look at Atlantic City. I think gambling’s been operating about seven years. During that time, they have put 15 of their public officials in jail for public bribery. Two of them have been mayors and 1 think four or five of them have been city councilmen. The others have been men who have been hired to regulate the gambling, to see that it’s run properly and that it’s run on an honest basis. The last man they put in jail just a few months ago was one of those regulators and he was trying to make a deal with some mafia representatives.

Look what gambling does to people who gamble. They become more desperate with each loss. I have a friend who was in the service with me. He owns a filling station in Vegas and while 1 was there attending a convention, I pulled in to get gas and we recognized each other. He showed me a whole box full of customers’ wrist watches that he had received in trade for gas to get home. They had lost everything they had. Some of the watches were Rolex’s. He told me that many times the gamblers will go to a used car lot and sell their car. Have you ever noticed the car lots in Vegas? They’re always full.

I just think that desperate people do desperate things. Somebody who might not ordinarily rob someone else might do it if he gets desperate enough. When people supporting gambling tell you that crime won’t increase, they simply do not know what they’re talking about.

Another thing is that I think gambling gives the people who really don’t have the money to gamble false hope. The people least able to afford to lose money frivolously are always the first in line. Most wage earners in our society live from paycheck to paycheck, so if they get behind, they have to take out a loan, then they get more behind. The overall effect on society is terrible.

Have you ever watched people play the slot machines? They get into a real frenzy.

Before we get too far off base, let me ask you about the slot machines. Once you finally began to seize them, they sort of became symbolic in your drive against gambling didn’t they? How many did you seize?

We destroyed 8,229 slot machines, and it’s really a funny thing the way we got into doing that. 1 went after the slots after the fee expired. I just issued an order for them to take them out whenever they were found.

I was unaware that the machines were to be destroyed. I knew that the law considered them contraband, but I did not realize the law required destruction, that is until a Grand Jury in Iberville Parish attempted to indict me for not destroying them. We had seized nine slots and just turned them over to the Sheriff and filed the appropriate charges.

So the Grand Jury sort of thought they had me in a crack. They thought it was funny because the law made it dear that nobody could possess contraband, not even a public official.

I was able to wiggle out of that bind by pointing out that the machines had been in the cafe adjacent to the courthouse for years, that I had had coffee with judges, the sheriff, other officers and public officials while sitting right in front of the slots. Nobody had ever said or done a thing, but 1 assured them that if the law required destruction, then they had nothing to fear, because 1 would certainly carry out that mandate. Of course, I’m sure, that’s not the response they wanted from me.

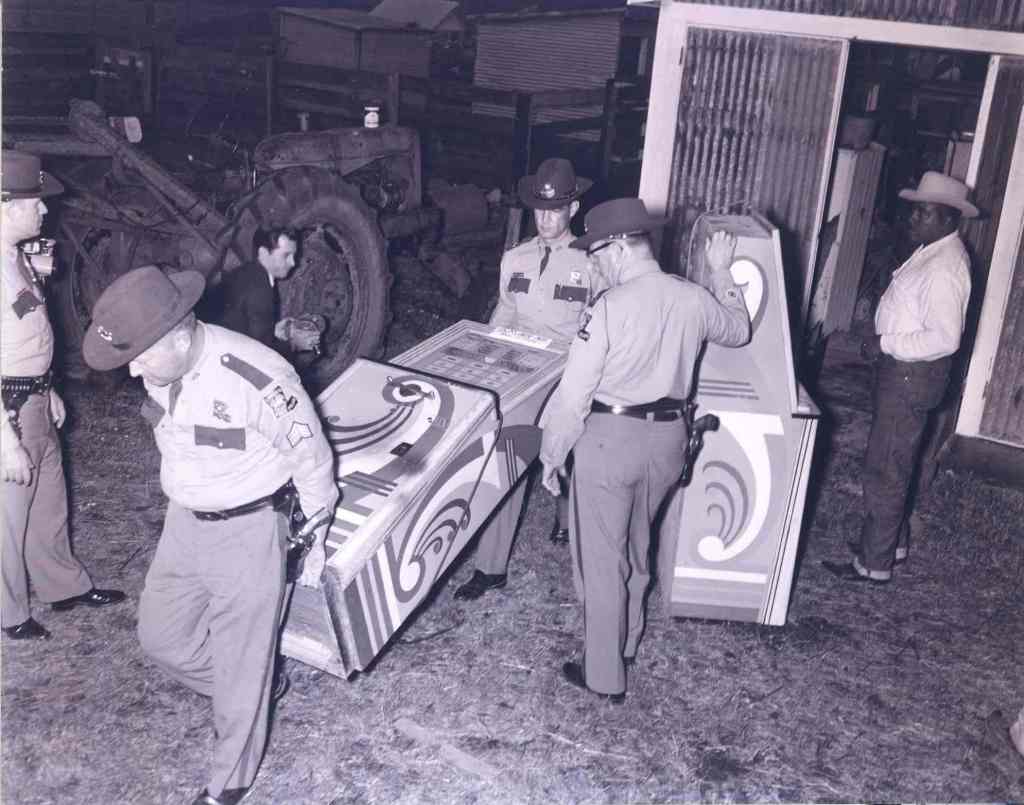

I left the courthouse and called for some troopers with mauls. Word spread fast, reporters and television people showed up and we all stood back while the troopers swung the mauls. We destroyed them all then and there.

What was your largest haul?

At one time we brought in 750 from Slidell. One of the machines had “Grevy” written across the top of it. I took a swipe at that one myself, but ordinarily I let the men handle the destruction. We piled up all of those and ran a bulldozer over them, back and forth, back and forth. The prisoners (at headquarters) and troopers were jumping around and grabbing nickels and quarters. I told everybody, wait a minute that money’s going into the Benefit Fund but they didn’t pay any attention.

A picture of that Caterpillar smashing the machines appeared on the AP wire all over the country.

Didn’t you wreck the gridiron show one year in Baton Rouge by seizing two slot machines used as props?

1 sure did. The show is put on by the Capitol Press Corps; they all dress up and make fun of the politicians and public officials. It’s all good-natured fun.

Well, anyway, this particular year the show was being held at the American Legion Hall in Baton Rouge. During the course of the show they had a skit with someone portraying me. He was dressed up in a boy scout uniform with short pants and all. Anyway, the skit involved the use of a couple of slot machines which were on stage. l knew that the machines belonged to Senator Horace Wilkinson. Horace was from West Baton Rouge Parish, very influential and we were bitter enemies.

Anyway, when I saw the machines, and knowing whose they were, l got up and went and called for a trooper and a city police officer. They called me up there to give me an award or something and when they did l simply took one machine in one hand and one in the other. Most people thought it was part of the show until I took them in the back and had the officers break them up. Wilkinson was raging mad.

Did you shock everybody?

Did I shock them, hell, it’s the only time that the Gridiron show made the national news. It was all over the country. I think it shocked Wilkinson more than anyone because he thought the joke was going to be on me.

Some people complained that you spent too much, or rather wasted too much time on gambling. The result, they said was an increase in highway deaths. Is that a fair complaint?

No. Some people said that right from the very beginning. They tried very hard to take the power and authority away from the State Police. They didn’t want us to have such power. They wanted us to be a highway patrol.

Who are “they?”

The Legislature. But the Louisiana Moral and Civic Foundation jumped right into the middle of things . They had every protestant congregation in the state writing letters to every one of the Legislators, and writing postcards to the governor. The message was clear, don’t change anything. It failed, but it was pretty damn close. Actually, that happened very early in my administration before I even really got started breaking up slots because they knew where I stood and what I had planned.

State Senator Horace Wilkinson accosted me on the floor of the Senate. He was about 260 pounds and after deriding me for my anti-slot machine activities he threw a right-handed haymaker at my chin and almost connected. I had boxed years ago and was still in good shape. He was so fat that I could have struck back before he knew what happened, but he was standing against the rail and had I hit him he’d gone over. I’m sure he’d have landed on his head and killed himself on the marble floor.

Did you sacrifice any traffic law enforcement in order to aggressively go after gambling?

No. I hadn’t backed off of traffic enforcement in the first year. Those claims simply weren’t true. During our first year in office we issued more than three times as many traffic tickets as were issued by my predecessor. We were able to prove that we collected over a million dollars in fees from the scales where the trucks were not being permitted to go overloaded or other-width or over-length on our highways.

Did fatalities go up or down?

Fatalities went down. I brought some innovation to our traffic enforcement, some things that the public wasn’t used to. By the time my second Fourth of July holiday rolled around, I had an airplane assisting in enforcement patrols.

Where did the airplane idea come from?

Well, we had one airplane when I took over and I used it extensively for staging raids all over the state. My pilot flew Spitfires during the Battle of Britain and later B-17s. Here he was flying this little Cessna 140, 40 miles per hour probably, tops. And one day while on a short trip in the plane I was watching the cars below and told the pilot, “If I could get a few more of these we could pre-measure distances on the road and dock cars with a stopwatch.”

It just amazed the motoring public. Not one person successfully challenged us. Every one of those tickets, the little guy would walk in like a man and pay his ticket.

Later after we were assisting corrections with an escape from Angola, we discovered how difficult it was talking to units from the air when you couldn’t identify them. So, we painted the unit numbers on top of the vehicles. It’s a simple idea but it made perfect sense. Now you see almost every police department do that. But, after 1 got out of office they took them off of the State Police vehicles. God, they didn’t want anything that was connected with my administration.

Before I left I had a plane in Baton Rouge, a plane in Alexandria, one in Shreveport and one in Lafayette. I had four. One pilot was a major, the others were captains.

Didn’t you also implement a program involving unmarked patrol cars? Wasn’t that controversial?

Yes, that was very controversial. The cars weren’t completely unmarked, but they were darned difficult to detect. The officers had a red light they used, red background, white letters that said State Police. The trooper was dressed in trooper pants, with his gun on, and was wearing a plain white shirt with a badge. From the side he looked like any other ordinary business man.

We only had one specially marked car per troop but 1 would use them and concentrate them where we had the most highways deaths, like on U.S. 61. They called that “bloody Airline Highway.” After using these cars for a while, the drivers out there really became Christians for a while. We gave ticket, after ticket, after ticket.

Shifting away from enforcement and operations for a minute, tell me how you accomplished your top priority, that is, how did you provide more money for troopers?

The troopers were making $175 a month; can you believe that? Well, on my second day in office I called the captain in charge of our fleet and told him that during my tour around the state l had seen a vehicle with 120,000 miles on the odometer. Needless to say, the car was in terrible shape. I asked him to do whatever paperwork necessary and have the vehicle traded in for a new one.

In a couple of days, he came back with a requisition and a bid price of $3250. I was shocked. I knew we had to have some heavy-duty equipment not on regular cars but $3250? So I asked, who all bid on the vehicle. He told me just the dealer we regularly got our cars from. The same one used by State Police for years. I told him to cancel that order and that bid, the price was just too high.

I did not understand why we had to use the same dealer year after year. Who says we have to buy just Chevys, or just Fords or just Plymouths. So l told the Captain to call for bids from small towns all over the state-check with whatever dealer is in Ville Platte, check with whatever dealer is in a small town in northeast Louisiana. Don’t check in Monroe, check in the small towns.

The first bid was for a Chevrolet from Ville Platte. It was about $1500 or there abouts. Naturally, when the regular dealer found out he wanted to know why I wasn’t doing business with only him. He told me that he’d always had the State Police business. And I explained how out of line his price was. His response shocked me, “But Colonel, I’m going to take care of you. You get $400 for each car you purchase through us.” I ran him out of my office. I told him never to bid on a State Police purchase again while 1 was there.

I later did the same thing for tires, batteries, radios, just about everything we had a need for. We saved enough money to give a raise to all our troopers. Before I got there, purchases, operating expenses were the largest part of the budget.

That’s uncanny. Usually personnel expenses are almost always the largest part of every budget. How much did you raise salaries?

I looked over my budget and raised them $100 a piece across the board, and this was before Civil Service. But Martin Fritcher came to me and told me that the troopers appreciated the money but $275 still wasn’t enough to make a living on. He told me he wasn’t griping but the men seemed to like the old system where they could shake people down, they could make a hell of a lot more money.

I told Martin, let the men know that their salaries were the most important thing to me, my top priority, but the old system just wasn’t going to be tolerated.

What other innovations are you proud of?

I was proud of the Junior Troopers. That improved our community relations and our image quite a bit. That didn’t last long, like many of my programs. But it was a good one.

I am also proud of the stock patrol. I implemented a system that permitted the animal patrol to operate and pay for itself; it didn’t cost the state one penny. I put Captain Dixon in charge of that and he did a marvelous job.

Another thing I think was new was to look at our assignments and determine if non-commissioned personnel could do the same job thus freeing troopers to do police work. I hired a number of handicapped people, people who otherwise would make great workers but couldn’t be troopers. I put 31 of them into the scale facilities freeing up 31 troopers.

Quite a few of the new hires were veterans of World War II and the Korean War. We also didn’t hesitate to hire people who were older than 55 to do some of these jobs. We saved a lot of money and ended up with more troopers enforcing the laws.

Even my secretary brought ideas to my attention. I had a soft spot in my heart for hiring young ladies at headquarters who really didn’t have much in terms of money. That is, they really needed the jobs to support families and such. I wasn’t aware of it but apparently women tend to become very competitive about things like dressing up and using make-up and such. I had no idea.

So my secretary and I decided that we would make a skirt, blouse and stockings available to each of them with a State Police patch on the sleeve, they would all be wearing the same things, no competition. There’d be more money for them to take home and pay bills. It was such a simple idea and the girls loved it.

What prompted you to run for governor?

People bothering the devil out of me, especially the Louisiana Moral and Civic Foundation. That was a great organization, it still is. They gave us lots of support when we needed it. l just wish 1 hadn’t listened when they urged me to run for governor.

During the time that I was trying to decide I had lots of second thoughts. I had spoken with many J. C. organizations, Junior Chambers of Commerce. ln every case they would come up and say look, we want to support you. We don’t think there’s another honest politician in Louisiana. As a matter of fact when l was giving a speech to the Lake Charles Junior Chamber of Commerce I announced that I was going to run for Governor, and man, the place went wild, standing ovation, the whole deal.

I said, gee whiz, maybe I’m not making a mistake. But I couldn’t raise any money. I had oil men who wanted to give me money, big money . My campaign manager told me that Mr. Jones (not his real name) wanted to see me and talk about money. So I went up to his office with my attorney. He insisted that we meet alone, which I did.

He told me that he wanted to back me for Governor and he was prepared to give me $50,000. I hadn’t even raised $10,000 yet and he was offering me five times that amount. I asked him what he wanted in return. He said, “Well, I want to appoint the Commissioner of Conservation and I want to appoint the chairman of the Mineral Board.” He didn’t want to recommend them to me, mind you, hell, he wanted to appoint them himself.

I declined the money and told him that if elected I intended to run government the way I had run State Police. As a matter of fact, I intended to impeach about 40 percent of the legislators. And I fully intended to do so too. So you know how long I would have lasted, don’t you?

A contemporary of yours, a reporter that covered many of the things you did back in those days, described you as a man that was really too honest for Louisiana, both in State Police and in government, that the people in this state would never be ready for a man like you. Is that a fair assessment?

I suppose that’s a fair assessment. Like that oil man offer, that happened four times to me. I wouldn’t take money from them. I would get on TV and ask people to send me $5, $10, $50 – send whatever you can. l told them that I only made $700 a month as Superintendent, otherwise, without their help I would not be able to compete with the others. God I hated asking for money, but I had no choice. I just don’t think an honest man had an honest chance at getting elected.

But I agree with you, I was not right for the people of Louisiana when election time rolled around.

What are your regrets? Do you have any regrets about your tenure with State Police?

Well, I’ve already told you that l regretted running for Governor. I just shouldn’t have let them talk me into that. Besides that I really regret that I didn’t take a harder line on some of the people that I inherited from the previous administration. There was no Civil Service protection for the dishonest ones who’d been stealing their way through their careers. That’s all some of them knew. God there were some crooked bastards who I left on the job and I guess I shouldn’t have let them stay.

I fired my share of troopers, and don’t get me wrong, I had some very fine men, but it was like a new chance, a new opportunity for everybody when l took over. I only brought in one guy from the outside, Edgecombe.

As an example of how bad things were you only had to look at our truck scales operations. It had become fairly common for troopers to skim money or require truckers to give them parts of their loads. So we set up a trap, sent some trucks through one of the scales one night, and confirmed with one of the truckers that went through that he had paid the trooper off. I pulled up to the scales facility and looked in the window. The lieutenant and two others were in there drinking, which they shouldn’t have been doing either.

Anyway, the lieutenant’s car was unlocked so I reached into the window and blew the siren and it just screamed. The lieutenant came running out of the building and said, “That blowjob will cost you $100.” He didn’t recognize me on the spot but to make a long story short I fired him and his two cronies on the spot.

The next day, the uncle of the lieutenant, who was a state official called and demanded that l give his nephew his job back because he had 19 years on the force. I told him that I didn’t care if the guy had 29 years on the job, I would not tolerate such blatant dishonesty.

I probably should have fired some of Kennon’s political foes as well but l didn’t. Major Kavanaugh, for example, from north Louisiana. He was an admitted Long supporter. He even bragged about it.

I transferred him from north Louisiana and sent him to New Orleans. l gave him a job that wasn’t even supervisory in nature. He didn’t even have the responsibility of a desk sergeant. I eventually let him return to North Louisiana.

Looking back on your nearly four years as Superintendent, what are you most proud of?

I’m proud of the fact that I came out with a reputation of being honest. That’s the thing I’m most proud of; Most people with whom I came into contact with after leaving the State Police regarded me as honest above all else.

My mother, father, grandfather, everybody, used to try to drive it into me — the greatest thing you can be is an honest person. Honesty is the thing that you have to abide by, and that is what I have tried to be. I have taken it on like a charge, tried to pass it on to my sons. Because I thought that it was a charge to me, even from my grandfather because I was so close to him. Anyway, l think that is the thing that has helped me more than anything else.

It was comforting to me when I left government service and got back into private business, people helped make me successful in my mortgage insurance business because they trusted me. They knew my reputation for honesty.

I was the man who wouldn’t fix a ticket and I didn’t fix one ticket the whole time I was in office.

I am very proud of that reputation, I’m proud of my time with State Police, and I’m proud of what happened to State Police while I was there.