As lawmakers descend into Baton Rouge for the upcoming legislative session, they are steeling themselves for what will certainly soon be a protracted and contentious debate over tort reform, a more palatable euphemism than the more accurate term, ”corporate welfare.”

Prologue

Last year, the Bayou Brief, in the multi-part series “Wrecked,” chronicled the legislature’s debate over car insurance, unpacking the spurious and unsubstantiated claims that limiting an innocent victim’s access to the civil justice system would reduce the price of premiums in Louisiana and documenting a number of discriminatory practices that allow insurers the ability to charge drivers more on the basis of gender, credit rating, marital status, and even for serving on a deployment in the military.

Deployment Penalty: How Big Auto Insurers Hike Premiums on Returning Vets

Wrecked: A “Premium Reduction” Bill That Would Only Reduce Car Insurance Accountability, Protections for Injured

Insurance Commissioner Donelon Accepts $20K from Man Indicted for Attempting to Bribe NC Commissioner

In Louisiana, Auto Insurers Have a License to Discriminate

Careless Operation: Part One

Major Insurers Charge Louisiana’s Blue-Collar Workers More for Basic Coverage Than White-Collar Workers

The Task Farce: What a Missing Report Reveals About the Insurance Industry’s Failed Effort to Avoid Accountability

In Louisiana, Auto Insurers Charge Wealthy Drivers with a DWI Staggeringly Less Than Drivers with a Spotless Record but Poor Credit.

Careless Operation: Tort Reform and the Fight Brought To You By Big Tobacco

Driven Into the Ground

Wrecked: How Auto Insurance Takes Louisiana for a Ride

In Part One of this report, I begin by scrutinizing the validity and objectivity of those most responsible for promulgating the widespread belief that Louisiana‘s legal climate is somehow uniquely and singularly bad for business. Because two surveys in particular, the U.S. Chamber’s Institute for Legal Reform’s State Legal Climate Survey and the American Tort Reform Association’s Judicial Hellhole Ranking, have played an outsized role in creating this perception, policymakers and government officials should first consider whether their characterizations of Louisiana are grounded in accurate data.

I then consider the recent history of tort reform in Louisiana, focusing on the careers of two of tort reform’s most notable proponents, former Gov. Mike Foster and Louisiana Commissioner of Insurance Jim Donelon.

After considering the role former Gov. Foster had once played and the role Insurance Commissioner Donelon continues to play, in Part Two, I will turn our attention to the specific components of the bill soon to be considered in the legislature and the ways in which the bill’s leading supporters have grossly overstated their case and failed to disclose significant facts that contradict their central justification.

Finally, I will discuss four bills that were recently pre-filed by state Sen. Jay Luneau, arguing that all four represent both good public policy and a documented way to reduce premiums, particularly for those who confront institutional and societal discrimination because of factors outside of their own control.

But first it is important to know what, exactly tort reform actually means and who is behind the perennial campaign for tort reform in Louisiana.

At its core, tort reform requires we ask a simple question: Who is responsible for the damages of an innocent victim?

The War on Civil Justice

How Big Business and Industry Have Spent a Fortune Convincing Louisianians to Relinquish Their Legal Rights

There’s a sure-fire way to rile up nearly any lawyer in Louisiana, especially one who didn’t move elsewhere for law school: Tell them you think the state’s civil law system and its unique traditions are inferior and illogical.

Be warned in advance, though. There’s also a chance you’ve committed yourself to hear a lengthy soliloquy on the numerous reasons you’re ignorant and wrong. Today, Louisiana law is much more accessible to those not familiar with the state’s Napoleonic tradition than it once was, but for most of the state’s legal community, it’s still a point of pride. And there really is a compelling argument that Louisiana‘s system is better and more intuitive than the way they do things in the other 49 states.

It is also the reason much of the legal community in Louisiana is skeptical about the legitimacy of the rankings by conservative and libertarian-leaning organizations that denounce the state’s “legal climate” and smear it as a “judicial hellhole.” Are the people who make these determinations even lawyers, or are they just ideologues? And if they are lawyers, have any of them ever practiced law in Louisiana?

In recent years, both the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Legal Climate Survey and the American Tort Reform Association’s (ATRA) Judicial Hellhole rankings have received a significant amount of media attention in Louisiana, which both consider among the nation’s most terrible, rotten places to get sued. Conservative state legislators repeat these rankings as if they’re scientific fact (or, if you prefer, gospel truth). And other organizations latch onto them in support of their agendas, without bothering to know whether they’re grounded in fact. In recent years, LABI, the conservative business group, has aggressively promoted the Chamber’s survey and the ATRA’s rankings to their members and to the state’s press.

But the truth is that neither the survey nor the ranking are credible, peer-reviewed studies. They’re bogus, annual exercises in fake news, and they are each at the center of the campaign by conservative Louisiana legislators to justify depriving innocent victims of the legal rights currently protected by state law. Far from ensuring a better legal climate, the changes that these legislators are proposing would only exacerbate a two-tiered judicial system and disproportionately harm the state’s most vulnerable.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about the Chamber’s and the ATRA’s work is how easy it is to uncover the farce, which makes the Louisiana media’s willingness to present them as legitimate news all the more troubling.

I have written before about the Chamber’s survey, which argues that Louisiana’s “legal climate” is the worst in the nation. How did they make this determination? They paid 1,300 corporate lawyers who work at elite defense firms to answer a few questions on a poll. None of these lawyers are based in Louisiana.

What about the ATRA’s Judicial Hellhole ranking?

I’ll let Professor Elizabeth Thornburg of SMU Law, my alma mater, explain:

“Judicial Hellholes are selected in whatever way suits ATRA’s political goals. The choice is not based on research into the actual conditions in the courts.…[T]he point of the hellhole campaign is not to create an accurate snapshot of reality. The point of the hellhole campaign is to motivate legislators and judges to make law that will favor repeat corporate defendants and their insurers, and to spur voters to vote for those judges and legislators who will do so. … As well-founded, honest commentaries on judicial systems, [ATRA’s hellhole reports] are a major failure….

“(The) reports represent opinions as facts, use quotations and anecdotes in a misleading and manipulative way, omit bad facts, and misuse statistics.

“Reasonable scholars on all sides of the substantive and procedural issues involved in tort litigation have debated and will continue to debate difficult issues such as deterrence, insurance, proof of causation, procedural efficiency, the role of the courts, the limits of science, and best choice of decision maker. The hellhole reports add nothing to these thoughtful and nuanced debates; indeed, they debase that debate by misleading and misinforming citizens and lawmakers.”

Again, because of the rigorous scholarship conducted by people like SMU’s Thornburg and Cornell Law professor Theodore Eisenberg, it’s not difficult to uncover troves of evidence that prove these rankings are bogus propaganda. In the rush for tort reform, we risk depriving ourselves of the only recourse available when the most powerful and wealthiest corporations in the world decide to trample all over our backyard.

Just ask former Louisiana Gov. Mike Foster.

Round One

Mike Foster’s Legacy and Legacy Lawsuit

Before the ink was dry on the series of “tort reforms” that Louisiana Gov. Murphy J. “Mike” Foster III signed into law in 1996, the state’s business lobby and a small handful of deep-pocketed conservative donors began clamoring for another round. This is not to suggest they weren’t satisfied with the first round; they were thrilled. Among other things, the new laws replaced Louisiana’s “strict liability” system with a “comparative fault regime” and “severely restricted plaintiffs’ ability to seek punitive damages” in cases involving hazardous materials and In auto insurance claims.

The changes had been touted as a “cornerstone victory” by allies of the state’s new Republican governor, who were certain the economy would flourish as a result. The insurance industry, which had pleaded for the new laws, promised that rates would go down as well, having vanquished their most formidable opponents- trial lawyers.

Foster, a wealthy patrician who earned a fortune in oil and gas and through his construction business and who continues to live on his family’s sprawling sugarcane plantation in rural St. Mary Parish, had just been elected to his first of two terms. On the campaign trail, he denounced what he called “jackpot justice,” arguing that lawsuits against oil and gas companies and auto insurers were stifling opportunities and driving away jobs.

A century before, his grandfather, Murphy J. Foster, Sr., had also served as the state’s governor and is best known for his shameful and long-lasting efforts to disenfranchise African Americans. Today, Mike Foster’s eight years as governor are largely remembered nostalgically and warmly, and to be sure, during his second term, the far-right wing of his party were less successful in influencing his policy agenda. His decision to enroll in Southern University Law’s evening program was widely mocked among white conservatives, many of whom were already skeptical of the young and increasingly diverse staff he had begun to assemble. (One of the most notable members of his administration was a Rhodes Scholar from Baton Rouge that he’d plucked from the consulting giant McKinsey to be his Secretary of Health and Hospitals. His name was Bobby Jindal).

Still, it is impossible to overlook the fact that during his first campaign, Foster had purchased a mailing list from David Duke, and only four days after he took office, he signed an order abolishing affirmative action programs in state government. The same day, he recognized Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, already a federal holiday, as a state holiday as well, a move that had been opposed by then-state Rep. Steve Scalise.

Even before he kicked off his reelection campaign, it became apparent that the predicted miracles of tort reform never quite materialized, at least when it came to the state’s bottom line. By 1999, Foster lined up behind a proposal to increase business taxes, and the very people who had been singing his praises after tort reform were now outraged.

After he left office and retreated back to his family’s plantation, Foster discovered that the mammoth oil company, Exxon, had damaged and contaminated his land, and in what may be considered the most ironic (or most hypocritical) decision of his entire professional career, he hired one of Louisiana’s sharpest and most successful trial lawyers, Glad Jones, to file suit against Big Oil itself.

“He’s the governor who took away punitive damages in April of 1996, soon after he got into office,” Jones told the Daily Advertiser. “But on behalf of his family partnership, when he discovered the damage that had been done to his property as a result of 50 years of oil and gas activities, he was left in no other position really other than to bring a lawsuit asking the oil companies to clean up the property.”

The case was eventually settled, but only after a protracted and contentious series of court hearings. “You think maybe that they would say to Mike Foster, ‘Look you worked with us back in 1996, and we’re going to come in and get you cleaned up.’”

Saying the Quiet Part Out Loud

The Insurance Lobbyist Who Told the Truth

“I think it’s a misnomer to every really believe that your (car Insurance) rates are ever going to go down,” – Kevin Cunningham, an auto insurance industry lobbyist, April 24, 2019.

Last year, at least initially, the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry (LABI) had been reluctant to use the term “tort reform;” this year, however, they’ve dropped the pretense. While there is no documented evidence that the bills proposed by LABI-aligned legislators have any correlation with the price of premiums, we do know that ending these discriminatory practices has been proven to result in cost savings.

Kevin Cunningham had been attempting to answer a simple question from Louisiana state Sen. Rick Ward III. “Have there been any things done in other states that have seen their rates (go down)?” Ward had asked.

“There’s so many pressures for (rates) to go up,” Cunningham said. “Medical costs continue to go up; the cost of a vehicle continues to go up; the amount of wages that you have to compensate people for continues to go up. So, maybe what you do is slow the rate of rise, but to say that you’re going to have something that’s going to bring the rates go down when there are other factors that make the rates go up is somewhat difficult.”

Perhaps unwittingly, Cunningham said the quiet part out loud, revealing a central truth about how the auto insurance industry operates in Louisiana: No matter what, the industry will turn a hefty profit.

As LABI and a faction of lawmakers ramp up their campaign in advance of the upcoming legislative session, it is worth reflecting on what their previous efforts exposed about the auto insurance industry in Louisiana and even more critical to consider the effects that their proposed tort reforms would have on our civil justice system.

If you include only the coverage that drivers are mandated to carry, Louisiana ranks as the fourth most expensive state in the nation for car insurance; if you add up the price of optional coverage, it’s the second most expensive state, directly under Michigan, the cradle of the American auto industry. For all of the tergiversation and the refusal to acknowledge the industry’s responsibility over its own business practices, the states with the most expensive car insurance premiums all have different legal frameworks.

However, there is a simple and direct reason Louisiana’s rates have soared: The state agency responsible for enforcing regulations and ensuring the marketplace is fair, competitive, and accountable has been more interested in protecting the profits of insurance companies than in protecting citizens from exploitive practices, a symbiotic relationship between government and business also known as “regulatory capture.”

Following the abolishment of the Insurance Rating Commission in 2008, Louisiana’s auto insurers are no longer subject to the scrutiny of consumer watchdogs, and as a consequence, the industry has not only been able to operate with minimal oversight; they’ve also controlled the narrative. So, it should be little surprise that when critics started making noise over the state’s expensive rates, the industry and its conservative allies refused to take any responsibility. The problem, they asserted rather conveniently, was Louisiana made it too easy and too lucrative to sue them.

Cunningham, as it turns out, was only partially right: A few months after his testimony in April, three of the state’s largest auto insurers, State Farm, GoAuto, and Farm Bureau, announced, seemingly on a whim, they would be cutting their rates on car insurance, a decision that had nothing to do whatsoever with the machinations of the business lobby. Ostensibly, the justification for the rate decrease was that all three companies had suddenly realized they were losing customers. They hoped that lower prices would lure in new business. At least that’s the spin they’ve put on it.

It’s just as likely that insurers were worried their most important ally was facing a tough reelection campaign. He needed a win, and they couldn’t afford to lose him.

Insurance’s Commissioner

The Career Politician

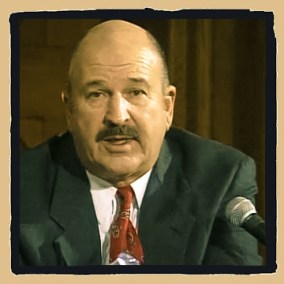

Louisiana Insurance Commissioner, James “Jim” Donelon III, doesn’t mind being called a “career politician.” After surviving a bruising reelection campaign last year, Donelon, 75, is set to become the longest-serving Insurance Commissioner in state history. Indeed, there are few people who have held political power for as long as he has. But arguably what is most notable about Donelon’s career aren’t the elections he won, but the ones he lost.

A native of Jefferson Parish in suburban New Orleans, Jim Donelon grew up around politics. When he was a teenager, his uncle, Harahan Mayor Tom Donelon, became the area’s most powerful official, Parish President.

But it was Edwin Edwards who gave Donelon his first big break, hiring him as his executive secretary when he was barely out of law school and naming him as one of only four people who were authorized to speak to the media on the governor’s behalf.

He was just 27 when he launched his first campaign, narrowly losing a race for District Attorney to John Mamoulides after briefly stepping down from his job in the governor’s office. Edwards would hire him back with a new title, executive counsel, a role that, in reality, was already occupied by the legendary Louisiana lawyer, Camille F. Gravel, Jr. Regardless, it was a job he didn’t keep for long. In 1975 and with his uncle retiring, Donelon had better luck when he ran for the Chairmanship of the Jefferson Parish Council.

Still, he was restless and in a hurry to win power before earning it. Toward the end his term on the Parish Council, he lost a bid for Lieutenant Governor to Bobby Freeman.

Following his defeat in 1979, Donelon, who was still considered a rising political star, aimed his sights even higher, running for the Congressional seat that Dave Treen left open following his successful campaign for Louisiana governor. Serving in Congress had always been his ambition, and when the opportunity presented itself, he fought hard for the job. Although he had always considered himself a conservative, Donelon didn’t change his party affiliation to Republican until early 1980, no doubt inspired by Treen, who had become the first Republican elected to the state’s top job since Reconstruction.

Edwin Edwards endorsed his opponent, another ambitious young politician named Billy Tauzin. Tauzin would sail to victory in the runoff, and Donelon, now nearly out of options, eventually made his way to the state legislature, where he’d remain for more than 17 years.

In 1998, Donelon would throw his hat in the ring one more time for federal office, challenging the incumbent Democrat John Breaux for a seat in the U.S. Senate. By then, it became evident that Donelon’s hyper-conservative and increasingly erratic politics were well outside of the mainstream, even in Louisiana. Among other things, he campaigned on a promise to abolish the Internal Revenue Service.

John Breaux trounced Donelon so badly that when he ran for district judge in his home parish the following year, he lost that race as well.

It was in the state House of Representatives where Donelon first began fashioning himself as an insurance expert. He’d admired the way Tauzin, his former foe, had become an authority on the oil and gas industry, and he hoped to do the same with insurance.

Following his unsuccessful campaign for judge, Donelon took a job as the Deputy Aide to Louisiana Insurance Commissioner Robert Wooley. He liked to boast that he was Wooley’s “Dick Cheney,” which would only seem self-deprecating if it hadn’t already been well-known that Vice President Cheney was, at the time, considered more powerful than the President himself.

When Wooley stepped down from office in 2006, joining the civil defense law firm, Adams and Reese, to work on insurance regulation in the aftermath of hurricanes Katrina and Rita, Donelon was automatically appointed Commissioner. He has subsequently won the job in four consecutive elections.

Now an elder statesman, Donelon has at times been the beneficiary of a public and a media that simply wasn’t around to witness the outsized sense of entitlement and naked ambition that had characterized his early career, and in the 22 years since his loss to John Breaux, Donelon’s brand of radical corporatism has been somewhat obscured by the dull and esoteric parlance of insurance-speak. Today, hardly anyone remembers that Donelon, as a legislator, had given a Tulane Legislative Scholarship to his own daughter.

Donelon claims he has the job he wants and that he’s perfectly okay with the fact that he never realized his dream of becoming a member of Congress. But when he recently spoke about not being recognized by anyone outside of his home parish, it was difficult not to hear the melancholy in his voice. Jim Donelon, after 45 years in public office, still occasionally and unwittingly reveals himself to be a man who got into politics not necessarily because he wanted to be powerful but because he wanted to be popular.

Although he speaks confidentially, albeit somewhat didactically, on what is presumably his expertise, insurance, it is usually within the context of a kind of autobiographical history lesson. He is far less comfortable and in command when addressing the mechanics of the business, and he struggles to articulate a coherent set of public policies or when he is asked to explain the actuarial analysis that justifies the industry’s antiquated and discriminatory practices. On one issue, though, Donelon is abundantly clear: He is cozy with the insurance industry, and though he denies it, the industry isn’t just enthusiastically supportive of the key changes contained in the proposed “tort reforms;” industry representatives were a dominant presence during the meetings of a task force that had been hastily put together to make recommendations on changes in state law that they believed would decrease costs.

Tellingly, though, the finished product didn’t turn out the way they had hoped. Even though they had stacked the task force’s actuarial subcommittee with the industry’s own actuaries, the subcommittee struggled to find any significant savings. In fact, the subcommittee’s findings were so embarrassing that the task force’s chairman, Kirk Talbot, concealed it from his legislative colleagues for nearly a month.

Recently, during a presentation at the Baton Rouge Press Club, Commissioner Donelon grossly exaggerated the subcommittee’s findings, claiming the savings would be exponentially larger than predicted.

To be sure, it took Donelon a little bit of time to realize he hadn’t gotten the same set of talking points as the other members of the task force. When he was first asked by members of the task force about what was causing Louisiana’s rates to be so high, Donelon named three “exclusive“ factors: “distracted driving, cheap gas, and cost of repairs.”

“The good news,” he said, “is that we have seen a stabilization of the rate increase trend.”

A year later, he was now certain the true cause: Lawsuits.

As Sue Lincoln reported on Monday, during the previous election, Commissioner Donelon’s campaign received at least $500,000 and potentially more than $1 million from insurance companies, brokers, agents, and associated PACs. Prior to last year’s election, Donelon had raised $680,000 in campaign contributions from the insurance industry, including a total of $20,000 from a man who had been indicted for allegedly attempting to bribe North Carolina’s Insurance Commissioner.