Prologue

On the eve of Louisiana’s jungle primary, the state’s two leading Republican gubernatorial candidates are hoping that a last-minute push by President Donald Trump can catapult one of them into a runoff against incumbent Gov. John Bel Edwards. But while a beleaguered Trump remains popular among Louisiana’s conservative base, partisan politics may only go so far in a state finally emerging from the disastrous and divisive leadership of Bobby Jindal.

During the past year, no other news organization has published more exclusive, in-depth investigative reports about the two Republican challengers, Ralph Abraham and Eddie Rispone. Veteran political reporter Sue Lincoln traveled to Richland Parish to get a first-hand perspective and insight into the sparsely-populated pocket of northeast Louisiana that Rep. Ralph Abraham calls home. She camped out at the Louisiana Secretary of State’s office during qualifications, and she questioned the candidates during a recent forum. Meanwhile, I took a deep dive into public records, archival material, financial reports, and even genealogical research. I may not be the only writer in the state who actually read Eddie Rispone’s first and only book, but I am definitely the only person who bothered to write a book review about it.

Together, Sue and I provided much of the research and information that would become critical components of the public discourse, but because we began publishing much our work several months ago, I have compiled this final, comprehensive report that contains our most significant findings, with the intention of helping voters in Louisiana become better informed about the choice they need to make tomorrow.

Lest Ye Be Judged

“I don’t judge people. I just don’t do that,” Louisiana gubernatorial candidate Eddie Rispone replied during the third and final debate ahead of Saturday’s jungle primary election. Rispone is diminutive in stature and speaks in a high-pitched, adenoidal tone with a faint Cajun accent. When he announced his candidacy shortly after Labor Day last year, he’d been completely unknown outside of the business elite in his hometown of Baton Rouge and a small circle of conservative political operatives. But he’s spent millions of dollars from his own bank account on a quixotic bid for governor, drawing comparisons to Ross Perot, the self-made billionaire from East Texas who became a household name during his run for president in 1992, and as a result, he is now locked in a statistical tie for second place with fellow Republican Rep. Ralph Abraham.

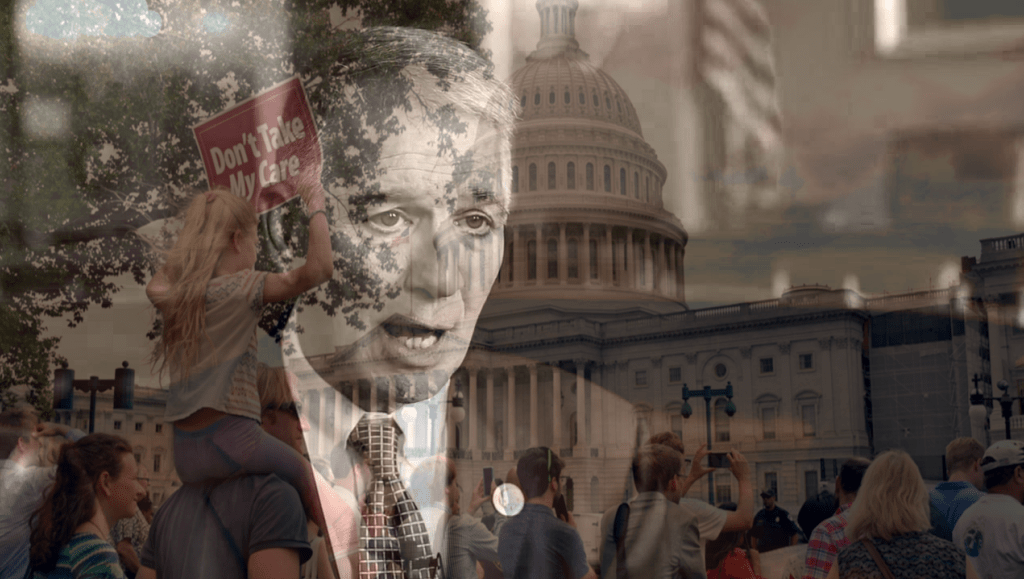

Rispone’s campaign has run the most inflammatory ads in an already-heated election. “Dangerous, sick, violent, John Bel Edwards put them back on our streets where they robbed, attacked, murdered,” the narrator intones in a commercial smearing the governor for championing a package of criminal justice reforms in 2017. Among other things, the reforms, which sailed through the Republican-dominated legislature and won the praise and support of the state’s most influential Christian conservative organization, the Louisiana Family Forum, allows for the early release of a select number of people convicted for non-violent offenses. Rispone’s commercial may have been grossly misleading, but it is central to a playbook that has sought to stoke fear and resentment against racial minorities.

When Edwards was elected in 2015, Louisiana incarcerated more people, per capita, than any other place in the world.

“Louisiana’s incarceration rate of 816 inmates per 100,000 residents is almost twice the national average, three times Brazil’s, seven times China’s, and ten times Germany’s,” Loyola University’s Dr. Sue Weishar wrote in the 2017 report Prison Capital of the Universe. ”The impact of Louisiana’s bloated and costly criminal justice system on African American communities has been particularly devastating. One in 20 African American adult males in Louisiana is incarcerated, a rate exceeded by only six states. Although only 32 percent of Louisiana’s population is Black, 67.8 percent of its prison population is Black, the second highest proportion of Black inmates in the U.S.“

As a direct result of criminal justice reform, the state no longer leads the world; that inauspicious title now belongs to Oklahoma. However, all those jail cells emptied by the state criminal justice reforms aren’t lacking for tenants, because the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown has refilled them to overflowing, making Louisiana the new hub for ICE detentions, with approximately 8,000 of the nation’s 51,000 detainees being held at facilities within Louisiana’s borders.

Edwards isn’t the only candidate who has drawn criticism from Rispone. In late September, Rispone’s campaign broke its promise and launched a full-scale assault against Abraham, angering Republican officials like U.S. Rep. Clay Higgins and conservative talk radio host Moon Griffon. During the third debate, after declaring that he didn’t “judge people,” Rispone called Abraham a “liar.”

His comment about judging people was actually about one person in particular, Donald Trump. In his very first campaign commercial, Rispone spent so much time heaping praise on the president that many viewers never picked up on his name or even what office he was seeking. There was little chance he was going to be baited into saying anything negative against Donald Trump, even in response to a question about whether there were any moral disagreements he had with a thrice-married adulterer who was once caught on tape bragging about committing sexual assault and who illegally paid porn star and Baton Rouge native Stormy Daniels $130,000 to keep quiet about the sexual affair they had shortly after his wife Melanie had given birth to their son Baron.

Nope, no moral disagreements whatsoever from Rispone, a conservative Catholic whose campaign had recently run a commercial featuring the candidate seated next to an oversized cross while talking about his belief in the power of prayer and how he intended to follow God’s guidance if elected.

To be sure, Ralph Abraham, the country doctor who, prior to his election to Congress, believed that nearly half of his Medicare patients needed a prescription to an opioid he was selling at his nearby pharmacy, is also hoping that voters care more about his allegiance to Trump than about his vision for Louisiana. Both men have calculated that rigid loyalty to the president is a sign of strength, but as candidates hoping to become the chief executive of Louisiana, blind fealty to the head of the federal government looks weak and lazy, regardless of who is occupying the Oval Office.

And while voters may not judge the moral decisions of a candidate they ship off to Washington, D.C., they do care about the character of the person they send to the Governor’s Mansion.

During the past year, the Bayou Brief has published dozens of reports about incumbent Gov. John Bel Edwards’ two leading Republican challengers, because much like Edwards had been four years ago, both Ralph Abraham and Eddie Rispone were largely unknown prior to this year’s election, despite the fact that Abraham has served three terms in Congress.

But before we explore the most significant aspects of our coverage, some of which have been referenced by others in television commercials, direct mailers, and news reports, let’s consider the cautionary tale of the candidate who had seemed all but certain to become the state’s next governor only four years ago.

Victimcrite

David Vitter had gone into hiding for a week, but the story wasn’t going anywhere.

It was one of the biggest political scandals in recent memory, when the nation became first acquainted with Deborah Jeane Palfrey, better known as the “D.C. Madam.” Palfrey possessed a Rolodex of clients that allegedly included some well-known names.

On July 9th, 2007, we finally learned on one of those names: David Bruce Vitter, the Louisiana Republican who had first arrived in Washington after winning the House seat vacated by Rep. Bob Livingston, a man who was once on track toward the speakership until his own extra-marital affair was revealed. Vitter quickly distributed a statement, admitting and apologizing for committing ”a serious sin,” and then he disappeared for a week.

The story about Vitter broke at the worst time possible for at least two other people.

Rudy Giuliani had been assembling a team and lining up endorsements in preparation for his 2008 presidential campaign, and already, he was off to an inauspicious start. He was on the verge of naming Robert Asher, a Pennsylvania businessman, to lead the campaign’s efforts in the Keystone State before discovering that Asher had previously been at the center of a massive public corruption investigation. A month before, his point person in South Carolina, State Treasurer Thomas Ravenel, was convicted of distributing cocaine, a charge that carried a maximum of twenty years behind bars. And then there was Bernard Kerik, the former New York City police chief that Rudy had recommended for Secretary of Homeland Security to President George W. Bush and who had just been sentenced to prison for federal tax evasion.

So, the Giuliani campaign already had been associated with a corruption scandal and a drug scandal. David Vitter, the campaign’s Southern Chairman, would link them to a prostitution scandal as well. Rudy’s campaign, which then-Sen. Joe Biden had characterized as “a noun, a verb, and 9/11,” was screwed.

Vitter came out of hiding on the 16th, holding a press conference at the Sheraton in Metairie. He was angry, strident, refusing to take any questions and quickly disabusing any speculation that he would be resigning from the Senate. His wife Wendy stood at his side, scowling at the press, and once her husband finished speaking, she took the podium. “To those who know me, are you surprised that I have something to say?” she asked. You didn’t need to know her; it was obvious from the moment she strode into the room.

David Vitter’s press conference streamed live across every cable news network in the country, and every major media organization in Louisiana, from Shreveport to Monroe to Acadiana and Baton Rouge, had sent someone to the Sheraton in Metairie.

The state media was supposed to have been at a different event that afternoon, right down the street. It’d been on the schedules of several in the press until the very last minute, when it became clear that David Vitter was a bigger story than Congressman Bobby Jindal’s announcement that he would be running for governor again.

It is impossible to understand the past dozen years of Louisiana politics if you’re unfamiliar with the Grand Organizing Theory of the Grand Old Party: Bobby Jindal and David Vitter can’t stand one another. Even today, they each serve as the titular heads of two competing political machines, though parts of Jindal’s machine were sold to Florida’s former governor and current U.S. Senator, Rick Scott.

Vitter, of course, had initially survived the 2007 D.C. Madam scandal, and when he stood for reelection in 2010, he trounced the Democratic candidate, Charlie Melancon, by 19 points, the same margin by which Trump would carry the state six years later. It had appeared nearly inevitable that Vitter would end up taking over the Governor’s Mansion once term limits sent Jindal packing for Iowa.

But Team Jindal would not go quietly. Those who didn’t join the “Louisiana mafia” in Rick Scott’s Florida coalesced around another Republican challenger in 2015: Former Lt. Gov. Scott Angelle.

Angelle and another Republican candidate, Jay Dardenne, who had replaced Angelle as Lt. Governor, would make it nearly impossible for Vitter to secure the majority he needed to win outright in the jungle primary. But Team Vitter made a strategic error; right out of the gate, they decided to spend a fortune pillorying the two other Republicans, torching whatever potential goodwill that could have existed.

Vitter would finish second in the jungle primary, behind Democrat John Bel Edwards, and during the general election, Scott Angelle decided to stay quiet; Dardenne, however, endorsed Edwards. Vitter was toxic; the prostitution scandal, after going dormant for the previous eight years, made a surprise move out of retirement.

Edwards clobbered Vitter by more than 12 points. Character mattered.

Dishonest Abe

Two days before Donald Trump’s arrival for a campaign rally in Lake Charles, ostensibly with the intention of somehow unifying voters behind both Republicans running for Louisiana governor, one of those candidates called the other a liar and a typical politician on live television in front of a statewide audience.

Eddie Rispone may have his own difficulties with the facts, but he wasn’t incorrect when he pointed out that Ralph Abraham was simply not telling the truth when he claimed that he has donated all of his salary as a member of Congress to St. Jude’s Hospital for Children and a charity that provides services and medical devices to wounded warriors, something he had pledged to do during his very first election in 2014.

In fact, earlier this year, after a member of his congressional staff unwittingly disclosed that Abraham would continue to draw his salary during a protracted government shutdown, he was forced to reluctantly confess that he had broken his promise years before. It’s not even clear he ever kept it in the first place; he has yet to provide any proof whatsoever of any donations.

At the very least, Abraham should have contributed $348,000 to the two charities, an irony not lost on his opponents when he recently loaned his campaign $350,000.

It’s difficult to imagine how any other elected official in the state could survive a broken promise as egregious as one involving hundreds of thousands of dollars for children with cancer and veterans who lost a leg or an arm due to a combat injury, and to be clear, when voters in Louisiana’s Fifth Congressional District sent Abraham back to Washington last year, they didn’t know Abraham had long since abandoned his pledge.

At first glance, it may seem insignificant, but considering the enormous influence the oil and gas industry has in Louisiana, it is also remarkable that Abraham has actually sued a pipeline company for damaging his land.

Ralph Abraham has learned how to wear his toothy grin as a shield, a way to deflect pointed questions and dismiss his critics, but he also carries himself with the awkward slouch of a teenager embarrassed by a sudden growth spurt. He speaks with the kind of lilting drawl that more skillful politicians can use to demonstrate both their relatability and their authority, but for Abraham, it only seems to exaggerate arrogance thinly-disguised as aloofness.

Prior to his election to Congress, he’d spent most of his career as his town’s only doctor, a role that immediately imbues a person with respect and a sense of entitlement, regardless of whether it is rightfully earned. And before became a medical doctor, Abraham had been a veterinarian. On the campaign trail, he claims to treat both farm animals and farmers, but Abraham hasn’t been licensed to practice veterinary medicine since Sept. 30, 2001.

He can be forgiven for creating the impression that his office was once a one-stop-shop for people and their pets; it’s provided him with more than a handful of clever punchlines, and ultimately, it’s harmless. He did, after all, graduate from veterinary school and medical school.

But his pledge to donate his congressional salary to charity isn’t the only promise he has broken.

During his first campaign, he vowed to shut down the small medical practice he had established in the tiny town of Mangham in Richland Parish. He’d made good money, he said, and he understood that serving in Congress was a full-time job. By law, physicians are required to provide their patients with at least 45 days advanced notice before they decide to end treatment or retire, but as the Bayou Brief exclusively revealed in July, Ralph Abraham never actually ended his medical practice, despite his claims to the contrary.

This year, on Father’s Day, Abraham shared a Facebook post from his daughter Ashley Abraham Morris. ”In recent years, my dad’s job has changed,” Morris wrote. ”He gave up a thriving medical practice to serve his country. It hasn’t been the easiest for our family. We’ve all had to make sacrifices.”

While it is true that a year after taking office, Abraham claimed his income from his medical practice had gone from nearly $350,000 to less than $13,000, both he and his daughter knew she wasn’t being entirely honest about the ”sacrifices” her dad had made in order to serve in Congress.

In reality, after waiting a couple of years, Abraham simply moved his practice a few miles up the road, opening a new clinic in May of 2017 in the nearby town of Rayville. Notably, according to documents filed with the Louisiana Secretary of State, the new clinic lists Abraham’s wife Dianne and daughter Ashley as its registered agents, but in financial disclosure reports, Abraham claims a 50% ownership share in the clinic. Neither his wife nor his daughter are licensed medical professionals; Ralph Abraham is the only medical doctor associated with the clinic, which employs two nurse practitioners under his supervision.

Moreover, Abraham never fully divested from his office in Mangham; he turned over operations to Affinity Medical Group and retained a 50% interest in the real estate, which somehow earned him between $50,000 to $100,000 in 2017, the same year his new clinic opened in Rayville. It was a staggering amount of money- presumably in rental income- for a small office building in a remote rural town home to only 638 people.

And none of this includes the income he has continued to earn from his pharmacies, something he conveniently forgot to mention when he campaigned for a seat in Congress. Don’t worry. We’ll get to the pharmacies soon.

Abraham’s decision to continue his medical practice, despite his attempts to disguise it as investment income or capital gains, isn’t a trivial detail. By all accounts, it is a flagrant violation of Congressional rules, which require members who are licensed to practice medicine limit their treatment of patients to charitable purposes or charge only the costs of their out-of-pocket expenses. In other words, once you’re elected to Congress, you’re not supposed to continue earning a profit from practicing medicine.

The reasons for this should be obvious: A physician cannot guarantee their ability to provide ongoing care for a patient if they also solemnly swear to “protect and defend and Constitution of the United States against enemies, both foreign and domestic” and to “bear true faith and allegiance to the same.” Medical doctors are singled out for a reason: Human lives are often at stake. It’s impossible for a physician to provide ongoing care when they also are bound by their obligations under the Constitution.

If a member of Congress decides to continue practicing medicine, neither their patients nor their constituents can command their full attention, something that Abraham has repeatedly illustrated, particularly during the past year.

Currently, Abraham’s congressional attendance record ranks dead last in the country. No other member has missed as many votes, an embarrassing fact for someone who flies his own airplane. And by his own admission, many of his missing votes, including a series of votes on the reauthorization of the critically important federal flood insurance act, weren’t due to his commitments on the campaign trail; instead of being in Washington D.C. to do the job he was elected to do, Abraham was back home in Richland Parish treating patients out of a medical practice he and his daughter claimed he had given up in ”sacrifice” to public service.

Make no mistake, though: He also missed important votes to attend fundraisers, even before he had announced his candidacy.

It’s still unclear why exactly Ralph Abraham wants to be governor or, for that matter, why he ever wanted to serve in Congress, but he embarked on a political career after being recruited by members of then-Gov. Bobby Jindal’s campaign machine to run against an incumbent Republican, U.S. Rep. Vance McAllister, a man who became nationally-known as “the Kissing Congressman.”

The Missing Congressman vs. the Kissing Congressman

Republican Party leaders publicly claimed they wanted to oust McAllister because he had been caught on video tape planting a passionate kiss on a staff member with whom he had been having an affair, but the truth is even sleazier: Someone had been spying on McAllister, and a camera had been hooked up to the office’s surveillance system with the deliberate intention of catching him in the act. Once they got the goods, it was handed it over to Sam Hanna, an outspoken conservative and the publisher of The Ouachita Citizen, an obscure outlet in northeast Louisiana. A year and half before the story of the “Kissing Congressman” went viral, Gov. Jindal had granted a pardon to Hanna, wiping away a criminal record that included four DWIs.

McAllister hadn’t earned their ire because of his extramarital affair. Instead, it was because McAllister, a self-made millionaire, came out of nowhere and defeated state Sen. Neil Riser, a key ally of Gov. Jindal, by emphasizing his political independence and his support for certain components of Obamacare, an unpardonable sin for the GOP establishment.

In Ralph Abraham, Republican operatives found millionaire physician who could speak with authority about his opposition to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, notwithstanding his obvious ignorance of the law.

There was only one obstacle in his way.

Vance McAllister had also been boosted by the endorsement of the region’s most famous native son, Willie Robertson of Duck Dynasty fame, but because of his scandal, McAllister was now off-brand for the star of a reality television show that emphasized wholesome family values.

Fortunately for the Robertson family, they didn’t need to beat up too much on Willie’s pal Vance, because cousin Zach had decided to run for Congress as well.

Zach Dasher, like his more famous cousins, marketed himself as a traditional, Christian conservative, but it didn’t take long to realize some of his beliefs were in a word… well… eccentric. He was 36 at the time, a married father of four small children, and after he dispensed the standard Republican talking points about God and guns, Dasher was prone to extended digressions about Thomas Hobbes and John Locke and his vague understanding of “natural law.” You know, the bread and butter issues for the voters of Louisiana’s Fifth District.

I remember the election well, because at the time, I was living and working in Alexandria. (For some reason, the only thing I ever wrote about Dasher on my former web publication, CenLamar, was a ridiculous, juvenile story about the cartoon character Darkwing Duck, which is unfortunate because Dasher proved to be a much more interesting character).

Even though they were both Republicans, Dasher wasn’t competing for the same votes as McAllister. Vance had gotten elected by cobbling together a coalition of working-class Republican moderates and African American Democrats in Ouachita Parish. There are compelling reasons to believe McAllister, despite the scandal, would have coasted to reelection if Monroe Mayor Jamie Mayo hadn’t entered the field. Instead, he presented the biggest threat to Dr. Ralph Abraham.

There is a reason Zach Dasher’s unsuccessful campaign in 2014 remains relevant today. For one, Abraham likely would have never been convinced to promise his salary to charity once he took the Oath of Office, but if you’re an astute political watcher, you may have seen the two ads Eddie Rispone’s campaign is now airing featuring Willie Robertson. In the first ad, Willie revealed he had no idea how to say Rispone’s ‘last name,” so in the next ad, he refers exclusively to his friend “Eddie.”

The title was the second ad was “Beard,” and while it is clearly a reference to Willie’s grooming decisions – or lack thereof – there’s a certain irony in the fact that word is also used to describe the opposite sex partner of a gay man.

It’s been five years since this election, and if you’re a really astute political watcher, you’ll know the answer to this question: How did Eddie Rispone earn an endorsement from and two television commercials with Willie Robertson instead of Ralph Abraham, who represents the Robertson in Congress?

I am not in the business of speculating about anyone’s private life, but I imagine the hostility has something to do with how the Abraham responded after reading this article.

Regardless of who first circulated a smear campaign against Dasher, but it doesn’t take too long to surmise what the Robertson family truly thinks about Ralph Abraham.

Welfare King

In 1980, the same year he became a veterinarian, the congressman’s father, Ralph Lee Abraham, Sr. passed away, leaving his 26-year-old son a sizable interest in the family’s 600-acre farm business. Although he sometimes downplays the farm’s success, it represents the single most valuable and most profitable asset in his portfolio.

According to Open Secrets, an organization that analyzes money in politics, Abraham is currently the 47th wealthiest member of the 435 member U.S. House, with an estimated net worth of $12 million. Without the farm he inherited from his dad, it’s unlikely Abraham would have ever become a multi-millionaire, and without the generous tax subsidies from the federal government, it’s unlikely the farm, which harvests soybeans and corn and grows cotton, would have never been able to stay in business.

Abraham, it’s worth noting, likes to call himself a “farmer,” but he has long since delegated those responsibilities to his son-in-law Dustin Morris, the husband of his daughter Ashley.

His congressional district ranks as the 10th most impoverished in the nation, and along with agribusiness, the region’s other economic engine is the private prison industry. There are very few opportunities for upward mobility, since someone else has already cornered the lucrative duck call sector.

When he was elected in 2014, nearly one out of four people in the district were uninsured, a fact that he dismissed when he declared his opposition to Medicaid expansion. During his first term, newly-elected Gov. John Bel Edwards reversed the decision of his predecessor, Bobby Jindal, and availed Louisiana of the $1.6 billion the federal government had set aside for the state to expand Medicaid, using a provider fee as a tax-neutral instrument to pay for the state’s match.

Since then, no other congressional district has benefited more from Medicaid expansion than Abraham’s, no thanks to him whatsoever. The district has experienced a double-digit decrease in the percentage of uninsured residents, and its local hospitals, some of which had been teetering on the verge of insolvency, have been stabilized; again, no thanks to Abraham whatsoever.

Abraham preaches from the Gospel of Bootstraps and the Epistle of Trickle-Down Economics, a set of beliefs that requires blind faith because there is no evidence it has ever worked in practice, despite its effectiveness as a talking point.

More than anything else, his antipathy toward the working poor has animated his politics. This March, at a luncheon in Natchitoches, he argued that Medicaid recipients could simply waltz their way out of poverty if they stopped “voting for a living instead of working.” And in September of 2018, he proposed enforcing a “work requirement” for those receiving food and nutrition subsidies.

His proposals have never amounted to serious policy prescriptions; they are mean-spirited gimmicks that appeal almost exclusively to his fellow white conservatives, and in a district in which more than one-third of residents are African Americans, they may not be a duck call, but they’re definitely a dog whistle.

They are also brazenly hypocritical, because not only did Ralph Abraham inherit the bulk of his wealth and grow up with the privileges often necessary simply to be admitted into veterinary school and medical school, both he and his family have collected more than $2.6 million in federal farm subsidies, the kind of program that, when provided to the working poor, is known as a government handout or welfare.

Late last year, after Donald Trump imposed a series of tariffs on Chinese products, China retaliated by implementing tariffs on, among other things, soybeans harvested in the United States, which just so happen to be one of the most important crops for Abraham Farms.

This year, we published more investigative reports on Abraham than on anyone else, and we were continually surprised by the seemingly endless supply of alarming and previously unreported information we unearthed. While the story about his broken promise to St. Jude’s Hospital for Children and a veteran’s charity was first reported by the Advocate on Jan. 17th, I had been provided the same tip a week prior and had written a report on Jan. 16th that languished in the Bayou Brief’s draft folder when a news alert appeared on my phone.

A few months later, though, I uncovered what, to me, is the most significant story of the year about Rep. Abraham, one that didn’t originate from a tip but from a simple question I asked a friend: Will you check Richland Parish?

The Pharmer and His Pharmland

Although I later learned that reporters with the Advocate had also been looking into the opioid prescriptions filled at Ralph Abraham’s two pharmacies, and truth be told, while breaking a big news story is something almost every writer relishes, I would have preferred if the Advocate had taken the lead. (They would eventually publish their own report, which included additional research I hadn’t encountered).

The Bayou Brief has, on occasion, reached more than 120,000 readers a day (and earlier this year, reached a half a million in a 24-hour time period), but the Advocate is Louisiana’s largest paper, and, with the recent purchase of the Times-Picayune, its reach is unrivaled. This was a big story; it deserved the biggest audience possible. To be sure, once I was confident that I had the story, I wasn’t going to stand by and wait for permission. I could only hope that the paper wouldn’t make the same mistake it had in 2014, when its editors decided to kill a report about U.S. Rep. Bill Cassidy, who running for Senate against three-term incumbent Mary Landrieu, failing to account for his time working as a physician at the old Earl K. Long charity hospital. I picked up on the story they had refused to run, and it generated national news and triggered an internal investigation by LSU. At the time, the paper’s editors claimed they were concerned that releasing a sensational story so close to the election would be perceived as election interference, which, in my opinion, was a specious assertion. Not publishing a story is much more egregious, because it deprives the public and voters the ability to be fully informed.

That being said, before we consider the information about opioid prescriptions, it’s worth noting that prior to our series “Pharmland,” only a small handful of people knew Rep. Ralph Abraham owns a pharmacy in Mangham and retains an ownership interest in another pharmacy in nearby Winnsboro. It isn’t exactly something he ever boasted about, and he had managed to keep his involvement in the two businesses out of the paper, even though both businesses are listed, plain as day, on his personal financial disclosure reports.

So, after publishing my first report, one of the questions I received most frequently was, “How can a doctor own a pharmacy? I thought that was illegal.” The short answer is: While it presents all sorts of obvious ethical dilemmas, it’s not illegal. Maybe it should be.

In the first report, I specifically looked at the total number of opioid prescriptions that had been filled at Abraham’s two pharmacies and the total population within a 10-mile radius of each. I would later refine my methodology in order to draw more direct comparisons.

Pharmland Part I.

In Part One, we unpacked the basics that can be easily ascertained by consulting’ DEA’s database. For my first report, I relied on data uploaded to the Washington Post from the DEA; I subsequently learned of a more up-to-date database, and unfortunately for Abraham, the numbers were only increasing.

Based on my calculations, from 2006-2012, the seven years at issue in the DEA’s database, Abraham’s pharmacies ordered nearly 1.5 million doses to service an area of approximately 6,000 potential customers.

While most readers had been rightfully shocked by the enormous volume of these high-octane painkillers, others were more interested in attempting to complicate these basic, incontrovertible findings by introducing easily disprovable speculation (i.e. a resident’s lack of access to other pharmacies; the notion that 1.5 million doses, when divided by a larger denominator, didn’t sound as bad; and the belief that an abundance of opioids could be offset by a massive supply of all other types of medication.

Pharmland Part II.: Excuses for the Doctor

I tackled those concerns in Part II, taking a wide-angle lens at the opioid epidemic and specifically looking into Abraham’s own words about the drugs, During a Congressional primary debate, Abraham was asked directly whether he supported the medicinal use of marijuana. No, he did not, he explained, and then he swiftly pivoted to extol the incredible wonders of opioids. It was impossible not to wonder whether or not Abraham enjoyed a close, professional relationship with pharmaceutical reps.

Considering he has constructed much of his public persona and his campaign around his identity as a medical doctor (his campaign staff rebranded him this year as “Doc Abraham” and he ends nearly every public gathering and every tweet with the line, “Help is on the way”), voters may be surprised that Abraham, for some reason, decided not to pursue a year-long residency after graduation from medical school. Instead, he accepted an internship. It was not a minor decision. By forgoing a residency, Abraham also relinquished any chance he may have had to become board-certified. He would never become a specialist in any field.

It is also important to note that we can reasonably surmise that a significant number of the prescriptions he wrote were distributed and purchased through the pharmacies he owned. And while he may be capable of earnestly arguing that he has never written a prescription that he knew was unnecessary, it’s impossible see this arrangement as anything less than a perverse incentive for profitability, one ripe for abuse.

Pharmland- Part III.: Apples to Apples

I recognized the methodology I employed in the first report left some readers confused, so in Part III, I decided to make a much easier and more direct comparison. Instead of combining the volume in both pharmacies and attempting to divine the boundary lines of the two pharmacies’ service areas, I would look at only one of Abraham’s pharmacies, the one in Mangham, and I would compare it directly to the other pharmacy in Mangham, which was slightly more than a half of a mile down the street. An apples to apples comparison.

There was no way to argue with this analysis. Both pharmacies served the same community; there were around the same age and size, and they ordered the same medications.

I have been told this is the ugliest infograph in human history, but it makes all of the main points much more concisely than I can:

Finally, several people asked if there was any evidence of Abraham’s profligacy as an opioid prescriber. As a matter of fact, there is.

Pharmland- Part IV.: A Bountiful Harvest

Because of HIPAA, it’s impossible to get a complete picture of Abraham’s prescribing practices, but the government does collect and share information on a physician’s Medicare Part D patients, which offers a snapshot.

The data set begins in 2013, a year after the DEA’s data ends and a year before Abraham joined Congress. That year, Abraham doled out opioid prescriptions to a staggering 41% of his Medicare Part D patients, ranking him as the eleventh most prolific opioid prescriber among family doctors in Louisiana. Among family doctors, he was also the third most prolific prescriber of all medications. Remember, Medicare is only for those 65 years old and over, and for those determined to be eligible for social security disability.

By 2013, a growing consensus of medical researchers and professionals had acknowledged that prescription opioids were a leading cause of an emerging epidemic, Ralph Abraham paid them no attention, nor did he pay much attention to any of the medical breakthroughs being made with marijuana in pain treatment and palliative care. He was still all-in for OxyContin.

I do not believe Dr. Abraham truly understood the inherent risks involved in overprescribing powerful opioids. Instead, I’m left with the impression that he simply never did his homework. He may be a little lazy sometimes. Then again, what should one expect from a person who makes his living by taking a check from the government and from a farm he inherited from his daddy when he was 26? Discipline? Humility? Empathy? Self-awareness?

He may have complained about people who vote for a living, instead of working, but ironically, he is one of a small group of people who are paid to vote for a living, and he doesn’t care enough to show up for work.

Phony Rispone

In early July of 2018, a friend of mine in Baton Rouge passed along some gossip he had recently overheard. “Apparently, someone named Eddie Rispone is thinking about running for governor, but he hasn’t gotten the green light yet from his wife and family,” he said.

“Who?” Rispone’s name had come up only two months before in a report I wrote about a loophole that allows wealthy donors to voucher schools the ability to effectively avoid paying state income taxes, but I had no idea how it was pronounced. Ris-pohn? Ris-poh-né?

“I don’t know the guy,” my friend said. “I’m just telling you what the word on the street is.”

At that point, more than a year before qualifying began, the conventional wisdom was that Republicans would field a well-known candidate to challenge Gov. John Bel Edwards, the incumbent Democrat, but even though Rispone was obscure to me, GOP insiders knew him as an influential, behind-the-scenes powerbroker.

During the previous twenty years, he had contributed approximately $1.6 million to Republican candidates and political action committees, $1.1 million to influence state elections and $590,000 on federal races. In 2015, Rispone and his businesses had dropped a total of $170,000 in support of David Vitter’s unsuccessful campaign for governor.

Sure, he didn’t possess a household name, but he had more than enough money to buy one.

He made a mental note to keep him on my radar.

On August 9th, journalist Jeremy Alford sent an email to the paid subscribers of his publication LaPolitics: “RISPONE EYES GOVERNOR.” He would make it official shortly after Labor Day, though, at the time, the attention of the state’s political reporters had been almost entirely focused on the upcoming Congressional midterm elections.

Neither Sue nor I coined the nickname “Phony Rispone,” though I wish we had, even if it doesn’t neatly fit. Rispone is less of a phony than he is someone in possession of more money than common sense. It’s pretty clear he doesn’t know a damn thing about governing, despite his proximity to power.

It is possible, though, to be earnestly, even self-righteously, ignorant.

During the final debate, in a response to a question about whether he believed the law should be changed to prohibit campaigns from text messaging voters (one of the most asinine questions of the year and further evidence that Louisiana needs a debate commission), Rispone said he would leave that up to the F.A.A., though perhaps they should wait until after the Boeing 737MAX issues are all resolved. Perhaps he meant the F.C.C.? Or maybe he meant to say the F.E.C.? Either way, the answer revealed a confusion about the differences between state and federal authority.

But that was harmless fun.

What was far less amusing was when he vowed to completely freeze new enrollees to Medicaid, which would be catastrophic for thousands and thousands of families.

Rispone so thoroughly misunderstood the issues the state had faced with its antiquated Medicaid eligibility verification system- the result of a complete dereliction of duty by the outgoing Jindal administration- he convinced himself, seemingly on a whim, that, despite the problem being solved and the system being modernized, the entire program needs to grind to a halt. If he had his way, it’d be an economic and humanitarian disaster.

While he may not have much of a clue about what government actually does, to his credit, Rispone has some vague notions of what he would like for it to do, almost all of which would inure to the benefit of his company and the company of his friend, the man behind the campaign’s curtain, Lane Grigsby.

It is impossible to understand Rispone’s candidacy without first understanding the Deus ex machina, the would-be kingmaker, though, many familiar with the dynamic prefer another term: Puppet-master. But we’ll save the Great Grigsby for another day.

For now, the most important takeaway is that Rispone and Grigsby are both central cast members of a troupe that Sue Lincoln dubbed “the Erector Set.” Why the Erector Set? Because they are Baton Rouge-based construction magnates who play with the government as if it’s a toy.

Sue has written extensively about Rispone, and recently, she revisited some of her older reports and republished them in time for the election. There’s no need for me to retread or recapitulate her work, but if you haven’t read it, I encourage you to.

I have published a handful of reports about Rispone, including the report about his use of the H1-B visa program:

And his Machiavellian scheme to avoid state income taxes by changing the law to count the donations he makes to his own favorite Catholic voucher school instead:

If you live in Louisiana and watch television, there is a chance you’ve heard references to one of these reports.

Geaux Vote

Four years ago, most Louisianians were introduced for the very first time to a state representative from Amite who offered a breath of fresh air and a way out of the calamity left in the wake of the most unpopular governor in modern state history. Today, even though people can’t figure out whether or not his middle name is a part of his first name or his last name, the state government is finally clearing out the pond scum that poisoned our politics and nearly bankrupted our bank account.

“One day, the people of Louisiana are going to get good government,” Earl K. Long once quipped, “and they won’t like it.”

Uncle Earl was only half-joking. Louisianians do, in fact, want good government, but the state historically has put a premium on the business of politics instead of the business of governing. Edwards may not be the state’s most colorful or eccentric political leader, and right now, both in Louisiana and across the nation, that’s a good thing. He didn’t show up in Baton Rouge as a way of catapulting himself into national fame or simply to grandstand. He isn’t running a perpetual campaign, much to the dismay of some of his supporters. He asked for the job, because he thought he could do the job. He wanted to do the job.

Frankly, I have been following this election cycle more intently than almost anyone I know, and I still have no idea why Ralph Abraham and Eddie Rispone are running to become governor. They both seem to represent the remnants of an intra-party battle first led by men who cared more about the accumulation of political power than about protecting and serving the people of Louisiana. They haven’t presented a single original idea, a single compelling argument or policy prescription; they’ve both trafficked in fear and xenophobia and the well-trod roads of racial resentment. And in Louisiana, unfortunately, we’re familiar with the playbook.

Edwards is a Democrat, but he is not the hero of the left that some wish he would be. He never pretended to be, though. He’s trying to do something very few others have been able to pull off. He’s trying to turn the state back around from the arsonists who ransacked it. And even though changing the government is like moving a ship with a feather, our compass is finally working again.