(Editor’s Note: With qualifying for the 2019 state elections commencing in two weeks, we’ve received numerous requests to republish this Rispone backgrounder, originally presented January 22, 2019, under the title Erector Set: Not So Fast, Eddie.)

Along with his brother, he’s created a successful, respected, mega-million dollar company. He has also tried (and thus far failed) to create both a new city and a new school district.

Now, Eddie Rispone is using some of his personal fortune to run for governor, as he wants to create an “improved” Louisiana.

Louisiana’s last “businessman governor” was Mike Foster – but not for want of other business owners attempting to emulate his success.

Buddy Leach, president and CEO of Sweetlake Land and Oil Company, ran in 2003. A former state representative, former congressman, he placed 4th in the open primary, and the race was ultimately won by Kathleen Blanco.

In 2007, Walter Boasso – a state senator and owner of Boasso America Corporation (sold to Quality Distribution of Florida for $60 million during the course of the race) – made it to the runoff. It was a race notable for Boasso’s ads touting his rags-to-riches tale of starting his business with “a garden hose, a bucket, a brush, and a box of Tide.”

Bobby Jindal won, however.

Another businessman contended in the 2007 primary: John Georges, who ran as an independent. The chairman of Georges Enterprises, who subsequently bought the Advocate newspaper from the Manship family in 2013, placed third in the 2007 gubernatorial primary. There were rumors flying – right up to the close of qualifying and spread by his pollster and business associates – that Georges would run in 2015, as well. He didn’t, and no other “businessman” candidate entered the race last time, either.

And every few years, buzz begins about a possible political run by Jim Bernhard, a former chairman of the Louisiana Democratic Party. Though he has never followed through on the speculations, it’s become a regular rumor (raised again this past fall), especially since he sold the Shaw Group to CBI for $3-billion in 2013.

For 2019, Eddie Rispone is the man the Erector Set’s kingmakers want to enthrone as Louisiana Governor.

He’s the chairman of ISC Constructors, LLC, which he founded with his brother, Jerry, in 1989. (Jerry, by the way, has a son named “Lane.” We can only speculate, but perhaps…in tribute to Lane Grigsby?)

ISC is an industrial engineering and construction company, based in Baton Rouge, with divisions in Beaumont and Houston, Texas and Sulphur, Louisiana. They design and build electrical instrumentation and control systems for large industrial plants, employing approximately 2500 people. As of 2015, ISC was ranked number 19 of the top 50 electrical contractors in the U.S., with annual revenue of $329 million. Since then, the industrial building boom in Louisiana has provided ISC with more work and close to a half of a billion dollars in annual revenues.

Rispone’s wealth is great enough that his family foundation has assets in excess of $12 million, according to ProPublica. And he has thus far self-funded his gubernatorial campaign with $10.2 million of his own money.

Profiting From the System

With no intentions of casting any aspersions on Rispone’s business acumen, or the caliber of work performed by ISC Constructors, there is little doubt that he and his business have benefited greatly from Louisiana’s corporate-friendly tax incentive programs, although it’s difficult to quantify the exact dollar amount.

While ISC has participated in nearly every major industrial project constructed in the state over the past decade, they are sub-contractors. The company designs and installs the electrical components and control systems that run the machinery in refineries and chemical plants.

According to the Louisiana Department of Economic Development, from 2008-2016, ISC Constructors was a subcontractor on industrial projects that – all told – received more than $750 million in ten-year property tax exemptions under the Industrial Tax Exemption Program (ITEP).

Projects at Motiva, PCS Nitrogen, Shell, and Valero Refining created a combined total of 19 new full-time jobs. Other ISC-involved expansions — for Rubicon, TOTAL Chemicals, Exxon Mobil, and Marathon – created no new jobs whatsoever.

That should come as no real surprise because ISC is primarily in the business of installing new computerized technologies and automation equipment that reduces or eliminates the need for human operators. What they do for these industries is, essentially, geared to eliminating jobs.

ISC has, however, directly benefited from the state’s Enterprise Zone tax credits. For their work on the Sasol project in Calcasieu Parish, they’ve been receiving $2.5 million a year in payroll tax credits since 2014, plus rebates on sales and use taxes for the materials, machinery, and supplies used on the project. At ISC’s main headquarters in Baton Rouge, the addition of a new engineering facility, started in 2013, has netted nearly $3 million per year in payroll tax credits, plus sales tax rebates.

The LED website currently lists both of these as “active contracts”.

Additionally, Rispone and his wife Linda were the 2010 beneficiaries of $213,484.58 through Louisiana’s film tax credit program. They funded, as executive producers, a documentary titled “The Experiment” – about students in New Orleans charter schools.

“Education Reform” Insider

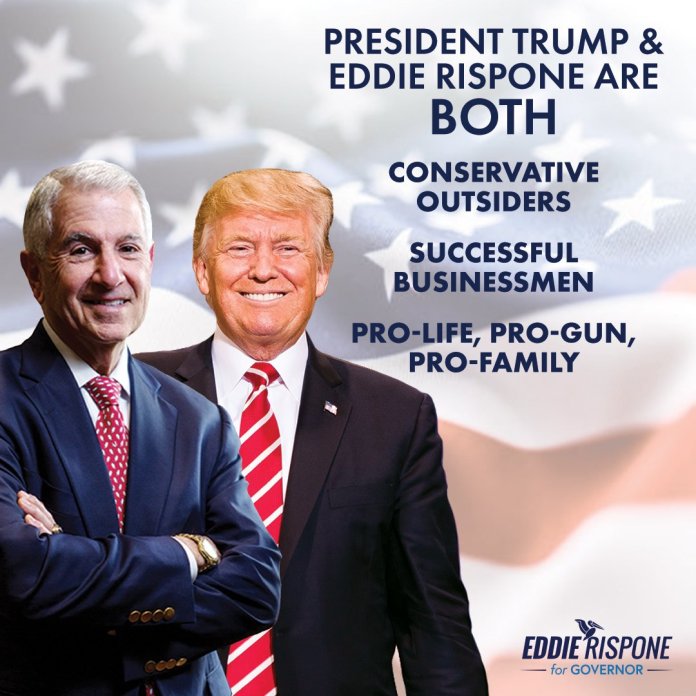

From the initial announcement that he was entering the governor’s race, Rispone’s campaign has pushed the concept that he’s a political “outsider,” while the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association’s Gifford Briggs referred to him as having a “fresh perspective.”

That’s far from accurate.

After all, political outsiders don’t generally fund and operate political action committees (PACs) of their own, nor contribute four, five, even six-figure amounts to candidates or other PACs. Rispone has been doing all of that for the past dozen years.

His entry into the world of political influence can be traced back to 1996, when he began developing deeper connections with the other two men now comprising the Erector Set. That year, Rispone was elected president of Associated Builders and Contractors Pelican Chapter, which Lane Grigsby had helped co-found in 1980. Art Favre served as one of ABC’s vice-presidents. In addition, that year, Rispone was named to the executive committee of LABI’s Board of Directors, on which Grigsby served.

Over the years, the trio’s companies have all contributed to ABC Pelican PAC, which Rispone’s son, Thad, now runs. Most recently, the PAC funded the Louisiana House Republican Caucus’s advertising and video campaign, through the four 2018 legislative sessions.

Okay, that’s relatively minor money and influence, especially when compared to the rest of Rispone’s political story. But it does illustrate the connections of the Erector Set cabal, and some of the strategy they’ve employed toward making the move to openly seek power in this election year.

Rispone’s first notable taste of political power and influence came after then-Gov. Bobby Jindal named him to chair the Louisiana Workforce Investment Council in 2009. That group, comprised of business owners, public officials, trade and labor group leaders, was tasked with finding ways to prepare for Louisiana’s future workforce needs.

And that was when they all began talking about the need for business and industry to “step in” and “assist” public education. The opportunity for business to profit – not just by having better-trained workers – but from the money taxpayers put into public education was too good to pass up. (As early as 2001, Ed Next – a publication of the corporately-funded EducationNext.org – had touted the potential in an article titled The Private Can Be Public.)

Louisiana had already made some moves in the direction of “education reform” (as the privatization movement is generally known), primarily in New Orleans, as financial necessity in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina facilitated the proliferation of charter schools.

During his first year as governor in 2008, Jindal – a devout Catholic – had pushed for lawmakers to authorize the funding of vouchers, ostensibly so disadvantaged New Orleans schoolchildren could attend parochial schools, with state taxpayers covering the tuition. Jindal hoped to expand the program, officially referred to as “scholarships,” statewide.

Rispone, also a devout Catholic, loved that idea and much of the rest of the “reform” platform. Along with Lane Grigsby, he then engaged in building some of the infrastructure that would help advance comprehensive “education reform” through Louisiana’s Legislature in 2012.

He and his wife Linda put $750,000 into producing The Experiment documentary, released in 2011. Like the more widely-viewed and well-known 2010 film, Waiting For Superman, it became part of the public relations campaign funded by education reformers prior to the 2012 session.

Rispone also started and chaired the Louisiana Federation for Children, a state chapter of the national American Federation for Children, defined by SourceWatch as “a conservative 501(c)(4) dark money group that promotes the school privatization agenda via the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and other avenues. The group was organized and is funded by the billionaire DeVos family, who are the heirs to the Amway fortune.” (Yes, that would be the same DeVos – current U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos. And on ISC Constructors’ website, there’s a July 2017 article boasting about a meeting Rispone had with the Secretary and the extent of their work together.)

Rispone was at the helm of the Louisiana Federation for Children PAC during the 2011 push to elect BESE members who would support giving John White the State Superintendent position, and the PAC also funneled money to legislative candidates who had indicated they backed “education reform.” The PAC spent $283,000 on those races.

The PAC lay fallow for the next three years, but in the election year of 2015, it started receiving large cash infusions, including contributions from DeVos and the Walton families.

Rispone and his wife Linda each contributed $100,000, and at one point, the PAC had more than $500,000 in cash. It again put money into legislative races, as well as spending more than $122,000 to support three of the candidates for BESE. But the biggest spending came in November 2015, during the gubernatorial runoff. LFC PAC spent over $265,000 on media buys opposing John Bel Edwards.

Shortly after Edwards’ inauguration, the Louisiana Federation for Children ran a TV ad campaign attacking the governor. They were upset over possible reductions to the statewide voucher program, which were being discussed – along with other cutbacks – as options for dealing with the budget mess left for Edwards by the Jindal administration.

At a Republican meet-and-greet earlier this month, Rispone admitted he had personally financed the attack ads.

And in the summer of 2016, Rispone started a second LFC PAC – the Louisiana Federation for Children Action Fund, seeding it with $150,000 of his personal money. Jim Walton contributed another $100,000 to the fund last month, which was Rispone’s last as chairman of LFC, and as the operator of its two PACs. He resigned from the organization in December 2018, due to his gubernatorial campaign.

“God Has Asked Me”

At the same Republican gathering this month where he confessed he’d paid for the 2016 ads hammering Edwards, Rispone told those in attendance his decision to run for governor – like his advocacy for school reforms – “It’s all about my faith.”

And as Melinda Deslatte of AP described Rispone: “He chokes back tears when describing a drive to try to help thousands of children who attend public schools deemed failing by the state, saying ‘God has asked me to do something about his kids’.”

That may play well with voters outside the capital region, but those who live in the Baton Rouge area identify Eddie Rispone closely with the “St. George” movement and all its undertones of white privilege. He’s been one of the biggest backers and funders behind the effort to carve out a new city – with its own school district – utilizing the Baton Rouge suburbs.

St. George and the School District Dragon

In 2012, the same year as the push for education reform, there was also a move to create a new school district within East Baton Rouge parish. State Sen. Bodi White filed bills to create Southeast Baton Rouge Community School System, which required a statewide constitutional amendment, plus separate approval by voters in the new district and voters in EBR parish as a whole. He also had a bill to allow creation of future separate school districts without requiring a constitutional amendment.

The new district would have grabbed ten schools, including the three newest schools built by EBR. The measures died on the House floor.

In 2013, Sen. White tried again. At the time, I was covering education for LPB, and I asked him about this seeming to be a move toward resegregation.

“We’ve been through a lot in this parish in the last 30 years, with desegregation, forced busing. There’s a huge distrust about the school system,” White said, the added it’s not about race – it’s about economics.

“Probably about half of the school-age kids in this parish go to private or parochial schools. It’s an economic concern. Can you afford to send your kids to another school? We can pay it, but it’s killing us. I can’t put any money in my 401K. I can’t put any money in their higher education fund. I can’t upsize my house. You take $30,000 or more – cash – for tuition out of our household budget – it’s crippling us!”

He was certain a new school district was the answer.

“The people who live in this area of the parish would love to be able to send their kids back to public schools.”

Again, no joy in the legislature for a new school district. So by end of 2013, the movement to create the city of St George was launched.

Albert Samuels, a political science professor at Southern University, observed, “Though the campaign doesn’t talk about it in these terms, a predominantly white and middle-class area of south Baton Rouge is attempting to secede from a school system and a city that is majority African-American. Instead, they have the temerity to say with a straight face that this has nothing to do with race.“

In 2014, Rispone put $100,000 into the Better Schools, Better Futures PAC, which supported the St. George city creation. That PAC was run by Lane Grigsby.

When the St. George initiative failed to muster enough support to make the ballot, Rispone created the Citizens for a Better Baton Rouge PAC with $125,000 of his own, plus more than $83,000 from fellow member of the Erector Set, Art Favre. That PAC ran ads and sent out direct mailings in support of Bodi White’s 2016 run for mayor of Baton Rouge. (White lost.)

Yet Rispone, who now claims his campaign for the governorship is “all about my faith,” has a real bone to pick with the activist church and community-based Together Baton Rouge, blaming them for the first failure of St. George. With a renewed initiative effort underway to create the new city, Rispone started a non-profit organization to counter Together Baton Rouge, called Baton Rouge Families First.

“Together Baton Rouge opposed a group of parents trying to get a better education for their children,” he said, when announcing the new non-profit. “It might have been called St. George, but it was really about giving children a better education.”

Rispone also admitted that, as a member of St. George Catholic Church, he was perturbed by his church’s membership in Together Baton Rouge’s coalition of pastors and congregations.

Acknowledging that TBR’s opposition to cookie-cutter approvals of ITEPs further incensed him, he questioned that group’s actions as an expression of its members’ faith, saying, “If Together Baton Rouge truly wants to help families you would think they would be working with their ally religious leaders in educating congregants about morals, virtues, independence and family life – the bedrock of a sound society.”

“All about faith”? “Educating about morals, virtues, family life”?

With all due respect, Mr. Rispone, what do your campaign contributions say about how much you truly treasure those values?

You and your company contributed more than $352,000 to David Vitter – his federal and state campaigns, and his Fund for Louisiana’s Future Super PAC – since the revelation and his admission of a “serious sin” in 2007.

In addition, you gave $100,000 to the Trump Victory fund, and you are clearly doing your utmost to hitch your campaign wagon to Trump’s star.

You might want to rethink that.

It’s the strategy Angele Davis used in the 2017 state Treasurer’s race, and she came in third in the primary.

Of course, with just three of you in the Governor’s race thus far, you’re guaranteed to at least match her third-place finish.