by Lamar White, Jr., with special appreciation for the assistance and insight provided by Michelle Riggs of LSUA and Thomas Whitehead of NSU.

In her late seventies and early eighties, Clementine Hunter was no longer a mere curiosity–– an illiterate, self-taught painter, born only a generation removed from slavery, a woman who had never traveled more than 100 miles away from the banks of the Cane River, the land where she was born and raised, and who had spent the majority of her life picking cotton before she ever picked up a paintbrush.

Her art may have still been dismissed by some as childlike and therefore unsophisticated, but by then, her critics were irrelevant. Hunter had established herself, in her own right, as an incomparable, important, and irreplaceable talent.

By then, a handful of Louisianian and national historians understood that Hunter’s artwork and the stories she told in her work were unique to a moment in the arc and the bend of American history; they were inextricably tied to a specific time and a specific place that would never come “back in style” like a sartorial trend. She hadn’t yet become an artist who could sell her work for tens of thousands of dollars or a woman now considered one of the nation’s greatest folk artists.

At the time, it may have been difficult to imagine that one of her paintings, “Black Jesus,” would become a part of the Smithsonian’s permanent collection.

It would have seemed even more astonishing to believe that an exhibition of her work at the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture would be its “largest collection of art we have by a single artist.“

Incidentally, like many of Hunter’s paintings, the “Black Jesus” that belongs to the Smithsonian is one of several of the same title. Arguably, her best expression on the theme belongs to the Alexandria Museum of Art (AMoA) in my hometown of Alexandria, Louisiana; it may be the museum’s most valuable jewel. (The AMoA also owns one of the best web addresses of any museum on the planet: www.themuseum.org).

If you pay close attention to the two works of the same title, there are a few details that may strike you as notable: For one, the painting now in Alexandria was created 22 years before the painting that now belongs to the Smithsonian, and then, notice the differences in Hunter’s signatures. These are not insignificant; they are small details that eventually become critical to an FBI investigation into a massive scam.

But in order to understand any of this, you must first understand what made Clementine Hunter so compelling, and to do that, you should allow her to tell her own story.

When I first conceived of this series for The Bayou Brief, I had not intended or planned to write any of the chapters myself. In subsequent chapters, we will share the scholarship and reporting of men and women who are truly subject-matter experts, but it quickly became evident that I would, at the very least, need to introduce Clementine Hunter to readers in a prologue.

Otherwise, there was a chance this series could be mired by an impulse to continually repeat some basic biographical facts: That she was a Clemen-teen, not a Clemen-tyn, that she lived until she was 101, that she was born in a plantation in Central Louisiana that was likely once owned by the man who inspired the fictional character Simon Legree in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s epochal book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In the prologue, I also briefly mentioned my great aunt- the sister of my paternal grandmother, Joanne Lyles White- Dr. Sue Lyles Eakin.

Dr. Eakin, like Hunter, also lived a long and consequential life, and like Hunter, she also left behind a series of invaluable contributions to Louisiana history, including, most notably, her scholarship on a book that had almost been entirely forgotten before she picked up a copy when she was not yet a teenager, Twelve Years a Slave.

As I mentioned in the prologue, Sue Eakin, who earned her doctorate in history when she was sixty, and Clementine Hunter, who began to paint when she was in her fifties, definitely knew one another, though they were a generation apart. I also knew that somewhere, buried in the massive collection of archival materials her children donated to LSUA, there were cassette tapes of the two women talking with one another.

LSUA is now in the process of digitizing these interviews and hopes to have some of them available for the public by the end of the month. When they do- and with their permission- I will update this chapter to include the audio. (To those wishing to hear Hunter in her own voice, I’ve attached a recording of an interview archived by Harvard University that was conducted in 1975).

In lieu of the audio, though, LSUA’s archivist Michelle Riggs provided me with a transcription of one of Dr. Eakin’s conversations with Clementine Hunter in 1974. While the 1975 interview offers a glimpse into the late artist’s cadence and wisdom, the transcription from 1974, which was completed in 2013 by a brilliant, young graduate student of Louisiana history, Meredith Melançon, gives us a less guarded and much richer understanding of Hunter’s sense of self and her story.

So, although we await the digitized version, the transcript still offers precisely what readers need first: Clementine Hunter in her own words.

Publisher’s Note: I have made a few, minor edits for formatting and clarity. On a few occasions, Dr. Eakin and Hunter make references to some of Hunter’s artwork.

After consulting with Thomas Whitehead, arguably the nation’s leading scholar on Hunter (buy his book, Clementine Hunter: Her Life and Art, co-authored by Art Shriver, here), I have included works that are at least representative of the ones referenced.

It will require additional archival research to determine whether the two women were discussing an educational slideshow, an LP record or tape recording with supplementary slides, or if they were merely discussing Hunter’s artwork in a more conversational fashion. Whitehead believes there likely was a slideshow accompanying their conversation, and if and when the show can be located and authenticated in Dr. Eakin’s archives, we will edit and augment this chapter to include it. All of the artwork that appears in this chapter was located in the public domain and is intended exclusively for educational use.

An interview with Clementine Hunter conducted by Dr. Sue Lyles Eakin in 1974, as transcribed by Meredith Melançon on Nov 19th, 2013. Courtesy of Sue Eakin Papers, Central Louisiana Collections, James C. Bolton Library, LSU Alexandria, Alexandria LA.

Portions of the interview are inaudible. When available, the interview was filled in with the text from the unpublished work Clementine: The Artist as Historian of Plantation Life by Sue Eakin. (Publisher’s Note: Whitehead also noted he had reviewed drafts of Dr. Eakin’s book).

Sue Eakin: We got to try and be quiet because . . . laughing . . . Clemetine tell us about yourself . . . tell us about where you were raised . . . born at Cloutierville and . . .

Clementine Hunter: I was born and raised at Chopin.

Eakin: Oh, at Chopin.

Hunter: Way down there in the Marco.

Eakin: At Marco, and Chopin, was that a plantation?

Hunter: Yes, that’s a plantation.

Eakin: Your daddy worked on the plantation?

Hunter: Yeah, my daddy farmed.

Eakin: And who did he farm for?

Hunter: I don’t know who he farmed for.

Eakin: Oh, it was somebody owned the plantation. Your daddy didn’t rent land?

Hunter: On no, he didn’t rent no land. He didn’t rent land.

Eakin: About how many people were there on the plantation?

Hunter: Oh, it’s been so long I don’t know exactly but they had a good many.

Eakin: Now this picture here was wash day. Tell us about what you remember about wash day.

Hunter: What I remember about wash day, you see them, that’s all they used to do. You know wash out under a tree. Well, if it was sunshine, you see we washed under a tree. And a long time ago they used to get them blocks and beat the clothes. That’s what momma and them used to do. Beat them clothes and then boil them. They called that cleaning them or something, I don’t know. Then they would rub ‘m on the rubboard.

Eakin: What were they blocks called?

Hunter: The blocks were called cypress, cypress blocks. Yea, it was round. Like that.

Eakin: Where’d they get the water?

Hunter: Out the well, out the cistern we called it, cistern. They got it out the well.

Eakin: With a bucket?

Hunter: With a bucket, draw it up with a bucket.

Eakin: A rope and a bucket.

Hunter: Yeah.

Eakin: You see, Clementine, these kids don’t remember anything about that. So that’s what we want you to tell them.

Hunter: Well, we sure did just get a bucket and a rope to . . . , out of the water, out the cistern, we called it. Not . . .

Eakin: Where’d they get their soap?

Hunter: The soap, they make it.

Eakin: Tell them that.

Hunter: Make the soap, you know, put lye, they get lye and grease and lye and make the soap. Let it stay there ‘til it get cold and it be just like the soap you buy here. We called that cold water soap.

Eakin: Cold water

Hunter: Soap. It’d be white and pretty.

Eakin: Where’d you boil the clothes?

Hunter: In a pot outside.

Eakin: Great big black pot.

Hunter: Yeah, I had one I don’t know what become of it.

Eakin: Yeah, let me try….

Hunter: That’s the white soap. I wash ‘em under the parasol. Didn’t have no tree for me to get under so I opened that over me while I was washing. I’m boiling my clothes right now in a black pot and rinsing them and hanging them out, you know. That other lady, she done dried some and she going home with hers on her head. She got hers in a bundle on her head. She going home with hers, theys already dry. And they, they lady is yet washing and boiling the clothes. She got to come back and get some more. In the same pot that I’m boiling the clothes in, that’s what you make, I take that to make the soap. When I ain’t boiling no clothes I make my soap in the pot. You put grease and lye, a lot of grease, old grease and lye and you take a stick and stir it up ‘til it get hard and pour it out and when it get cold you cut it with a knife just like . . . soap . . . that’s the way it looked like. It was white. It was white just like this P & G soap.

Eakin: Tell us about going to church.

Hunter: That’s an old man and an old lady going to church. She got her parasol and he got his stick, he walking with a stick. And . . .

Eakin: [faint questions] Did all the people go to church?

Hunter: Some of them, all of them go don’t go to church every Sunday but not all the services. One of them 7 o’clock, one 10 o’clock. All of them don’t go at the same time. Some go at 10 some go at 9. I goes at 9, to church.

Eakin: Clementine, talk about the little angels, even if they . . .

Hunter: That’s the sheeps, some little sheeps and a goose. That man yonder taking care. You see that? Goose. See that little sheep there? That’s a barn. That’s a barn there behind that man. I can’t see that. That’s me feeding my ducks, the goose. See that? . . . Feeding the goose. But she’s coming to the land.

That’s a Saturday night. That’s a Saturday night, that man shooting that one and that one got scared when they was fighting. They was fighting down there today to that hall and he got up on the roof with his bottle of wine. And he drink it because he was scared to drink it down on the ground. That one down on the ground beating the other one taking his whiskey out his mouth. And that old woman yonder fighting, fighting the other woman, pulling her hair, got her hair all down. And the other one drinking and the wine just wasting on her. Look at her wine. She look like I don’t know what drinking that wine.

Eakin: [laughing]

Hunter: They eating watermelons. They eating watermelons, two ladies. Sitting to the table eating watermelons.

Eakin: How’d they get the watermelon?

Hunter: They grow ‘em out in the field. In the watermelon patch. They has a patch with all the watermelon in it. Then when they get ripe they goes and gits ‘em and cuts ‘em and eats’em.

Eakin: What part of the year do they get ripe?

Hunter: They get ripe about, *when cotton open. Git ripe ‘long August, like dat. They get ‘em and cut ‘em and eat ‘em. He cuttin’ the watermelon. He cuttin’ the watermelon and fixin’ to eat it.

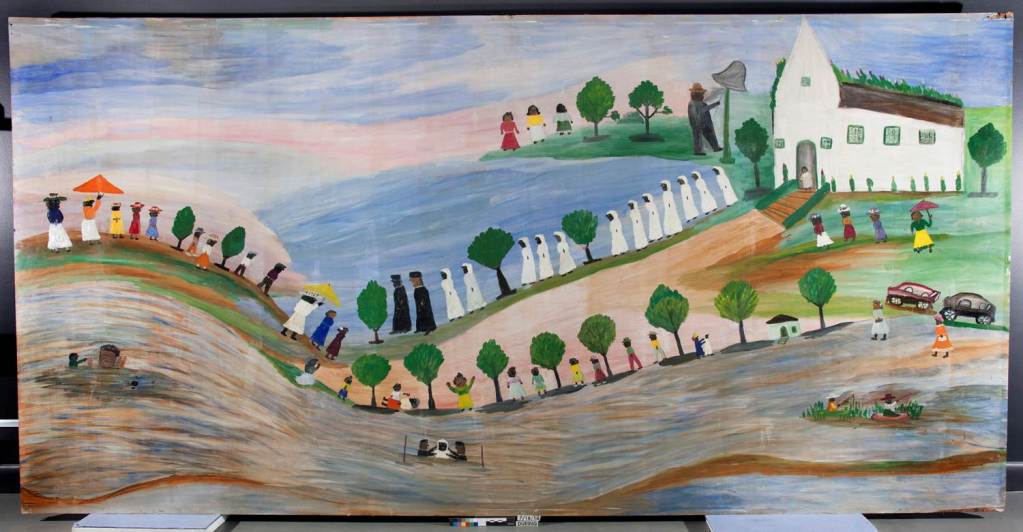

Hunter: That’s the African House and that’s the Calico girls.

Eakin: Why are they out here?

Hunter: They go to the African House. They going to have a tour when they all get there. They all ain’t there yet. That’s what they waiting on.

Eakin: What plantation is that?

Hunter: Melrose Plantation. That’s where they have the tour like every two days in October. They have that tour.

Eakin: inaudible

Hunter: Well, I been working since it started. I reckon about 15 or 16 years I been working there with them.

Eakin: You were a cook down there weren’t you?

Hunter: Yea, I cooked. I cook almost seven years. I cooked until the old lady died, when she died that’s quit. Didn’t cook there no more.

Eakin: Who was the old lady?

Hunter: Mrs. Henry.

Eakin: Tell me about her. What did she look like? Was she a nice lady?

Hunter: Yea, she was nice, she was good to me. She done got sick and died. And I just didn’t want to be there no more and I just left. That’s me painting. Got my brushes, got my paint on my lap and that’s the way I paint. I don’t have no easel or nothing. I don’t care to paint on that. I just paint like you see there. That’s the way I paint. I don’t paint no other way.

Eakin: Is that a photographer taking your picture?

Hunter: Yes, somebody. I don’t know who. Somebody taking my picture right now. I don’t know who it is.

Eakin: Who are those people?

Hunter: They is rocking in the other place. One wrenching clothes, and one washing, and what the other one doing? One boiling clothes. That’s off in the yard yonder. Somewhere in the yard and I’m painting under the tree. That’s where I’m painting. They stirrin’ the clothes in the pot. She done wrung hers out.

They haullin’ cotton. Haulin’ cotton and pickin’ cotton. Haulin’ cotton and pickin’ cotton. That old man don’t look good to me.

Eakin: How many mules does he have?

Hunter: One. One mule. He look like he gonna fall off of the wagon. [laughing]

Eakin: Did they have a lot of mules on the plantation? Tell them about it.

Hunter: Not too many. They didn’t have too many mules. Just a few mules. They didn’t’ have too many. Just enough for the people to haul the cotton with.

Eakin: Now, Clementine, if you will just tell them all you remember about cotton picking. The kids see the machines picking cotton. They don’t remember that people ever picked cotton. Tell them about it will ya.

Hunter: We picked cotton in sacks. We don’t pick with no machines now. I mean not no more. Cause when we used to pick cotton, I picked draggin’ my sack. That’s the way I picked it. Now they pick with machines. I picked it draggin my sack. And I picked three, I picked three hundred and fifty pounds of cotton a day. That’s what I was pickin. Three hundred and fifty, draggin my sack from 8 o’clock in the morning until 5o’clock in the evening.

Eakin: How much did they pay you for it?

Hunter: Fifty cents.

Eakin: Fifty cents a hundred?

Hunter: And they didn’t give no more than fifty cents a hundred when I was pickin’ cotton.

Eakin: How much would that be today? $3?

Hunter: I reckon. I don’t know. Cause I just picked . . .

Eakin: Two and a half?

Hunter: About two and a half because it was fifty cents a hundred. That’s all I was getting. And fifty cents a day for to hoe the cotton. Just fifty cents a day.

Eakin: All day long?

Hunter: All day long, fifty cents a day from sun up to sun down. Now you know we ain’t got to do that now, but they used to do it in them time when I was small.

Eakin: Did you take your babies to the field?

Hunter: I take my babies to the field, put them under a tree and put the water there and put their food their and leave them under a tree and I be working. That’s what I done with my children. Some people make out like now they got to have babysitters. I ain’t. I got mine in the field. Out in the field. Babysitters! I ain’t had none.

Eakin: What’s in the art here?

Hunter: That’s just a cart . . .

Eakin: . . . cart . . . riding . . .

Hunter: That’s just a cart to haul cotton. That’s a cart to haul cotton. That’s all.

Eakin: inaudible

Hunter: . . . Oh, that’s a sick man. That’s a sick man. That’s a nurse. He in the hospital. She givin’ him medicine. She feedin’ him. He can’t get up. That’s about all, I think.

That’s a Baptist church. The people are all gathering around to the church, to go in the church. Some to the door to go in and some standing around to go in. So that’s about all of that.

That’s Baptists. Baptizing in the Cane River. That’s a baptizing. That’s a Baptist Church, so. That’s all of that. They had one, two, three, four, five, six, seven to baptize.

That’s a gin. They ginning cotton. Ginning cotton and bales of cotton. That’s the bales of cotton and that man rolling the bales over. And that man yonder feeding the sucker.

Oh, yeah. Going to the funeral. They going to the funeral. In them times they carried the casket in the wagon. See in the wagon? And now, the ambulance come get ‘em. That’s in the olden times. That’s a long time ago where they would haul it to church in the wagon. That’s a burial. One man ringing a bell. Ringing a bell for them to bury the man. I say ‘man’ I don’t know what it is. Might be a woman.

Eakin: laughing

Hunter: Oh, that’s the weddin’. That’s the weddin’. Let’s see.

Eakin: Tell them about marrying and all that cause I don’t know . . .

Hunter: Well, I don’t know.

Eakin: In the church?

Hunter: Yeah, they married not in the church they married on the outside of the church. They had so many people they married on the outside. Some of them married on the outside, some of them married under a tree and all like that. They make it look like, you know, and that man. I don’t like the way he look. He don’t look so natural. But she like him. She like that man. But I don’t.

Well, that’s pickin’ pecans. That lady picking pecans. Well, she too old, look like, to bend down, her. She just picking one up at a time.

Eakin: Oh, that’s marvelous.

Hunter: Oh, she playing cards. They playing cards.

Eakin: Where are they playing?

Hunter: They playing on Melrose under a tree. That’s where they playing cards at.

Eakin: inaudible

Hunter: . . . that man there, that woman there, there’s two women playing cards. Shoot, three women, no two women. There’s three, yeah, there’s three. Three women playing cards. They going soon be fighting because they winning her money. Yeah, they winning all her money.

Oh, they got that man in the *go-run I called it. They going to kill him. See him sitting in that courthouse there? I be scared if I was him. Look at him? See . . . sitting there? They gonna get him. He killed a man. And now they got him. And he sitting just as straight in that chair. I’m telling you, you something else. That my house?

Eakin: Yeah. Tell me how long you been living here?

Hunter: Oh I been living in this house about thirty years. Right here in this house. Once I moved, I was staying to the spillway. A little, a place below Melrose. I was living in a house there. And I moved from there I moved here to this house where I’m living now. And didn’t do nothing but raise flowers.

Eakin: Is that all? Clementine, tell us something about yourself, all about yourself.

Hunter: I don’t know about myself.

Eakin: [laughing] You were born in Cloutierville and about when you started painting.

Hunter: Well, I don’t know exactly. I just painted. I don’t know. I just got to painting. Five, I had five children when I started to paint. I wasn’t no girl when I was painting. I just took that up like that, you see. I didn’t go learn nothing no where. I just picked up any kind of piece of board and paint, paint on it.

The Lord gave it to me and I just took it up. I didn’t know whether it was right or wrong but I painted.

Eakin: Tell what you painted, you know. You painted the life you knew, right?

Hunter: Well, yeah. I painted different things. Pecan picking and cotton picking. Different things that I know . . . I didn’t . . . I painted anything after that, just painted.

Eakin: You painted the people you knew about, right?

Hunter: I done made my own people. I didn’t know who people, I just made a person.

Eakin: I know but it was like people you knew.

Hunter: Oh yeah, just like people, uh huh.

Eakin: It was the way people lived . . . wasn’t it?

Hunter: Yeah, that’s right.

Eakin: Do you figure you’ve had a happy life, Clementine?

Hunter: I been having a happy life . . . I’m yet happy. If I just could do. But you know a person can’t do what they used to do. They got to take it easy now. Yes, I do.

Eakin: If a child would ask you how to paint, and how could they become a painter, what would you tell them?

Hunter: Well, I couldn’t tell them. I just couldn’t’ tell them because they just have to do like I do. The Lord done show me, you know, how to paint different things. I would mark it. I would see it in my sleep and I would get up and mark it with a pencil. My husband told me he said, you gotta be crazy, he say you gotta be crazy getting up at night fooling with a picture. And I would, I say , well, what I answer him, I say, what God gave you, you ain’t gonna go crazy. That’s what I told him. And I said I got to keep it up.

Eakin: Would you tell children to paint what they know or, how would you tell them?

Hunter: No, I wouldn’t tell them nothing about painting. None of the childrens.

Eakin: They Lord will tell them, huh?

Hunter: Yeah, I tell them sometimes. I say, they ask me, I said well I can’t tell you ‘cause some people done come here and ask me would I teach they children. I told them I couldn’t. I couldn’t teach the children ‘cause I couldn’t give them what the Lord give me. ‘Cause he might would take it from me if I was going to give it to somebody else. I can’t give it to nobody else. I got to keep it myself. That’s all.

Eakin: That’s wonderful.

Clementine Hunter interview with Dorothy Robinson, with the assistance of Thomas Whitehead, 1975; Harvard University archives.