On November 6th, Louisiana’s voters again face the decision of whether to make more amendments to the state constitution – six more, to be exact.

Since this state Constitution was enacted in 1974, it has been amended 189 times. Yet one of the reasons for composing this, Louisiana’s eleventh primary governing document, was because the 1921 version which preceded it had been amended 536 times.

Compare that to the United States Constitution. In 231 years, it has acquired just 27 amendments.

A constitution is supposed to outline the organization of government, set forth (and limit) governmental powers, and list citizens’ rights. We have other laws,, called “statutes”, which deal with nitty-gritty details of governance, including tax rates, special state funds, crimes, and the punishments for convictions.

With that in mind, let’s examine the proposed amendments, asking three questions of each:

What are we being asked to add, change, or tweak this time?

Is that modification appropriately done constitutionally, or can it be accomplished by statute?

And who will benefit if we, the people, say yes to the alterations?

The third question is important to the discussion, for many of the amendments previously added to Louisiana’s constitution were put there to protect special interests from legislative interference. As a result, we have a plethora of constitutionally-dedicated funds that can’t be touched, as well as constitutionally-protected tax breaks that have become sacred cows. And even though state lawmakers – by a two-thirds majority of each chamber – are the ones who write and approve amendments first, before sending them to the voters, state legislators have also been the loudest to complain that their fiscal hands are tied, due to these dedications approved by the people because we wanted to keep legislative hands out of the cookie jar.

Now, let’s look at the topics lawmakers have decided we, the voters, should be allowed to express our opinions and votes toward or against.

Amendment 1: “Do you support an amendment to prohibit a convicted felon from seeking or holding public office or appointment within five years of completion of his sentence unless he is pardoned?”

This is an issue voters addressed in 1998, just after four-time Gov. Edwin Edwards had been indicted on racketeering charges around the riverboat casino contracts. Voters then approved an amendment prohibiting convicted felons from seeking and holding office for 15 years after completion of sentence. In 2016, that amendment was thrown out by the Louisiana Supreme Court, due some language missing from the version voters saw.

Other laws regarding elected and appointed officeholders with felonies are statutes: removal from office if convicted of a felony, and a prohibition against seeking office while time remains on the original sentence – in other words, while on probation or parole. This particular prohibition could also be handled statutorily.

Technically, one’s “debt to society” is paid in full at the completion of the sentence. Of course, with certain sex crimes, ranging from flashing to child molestation, we require the perpetrator to register as a sex offender following completion of the sentence. We have – by statute – turned the punishment for those crimes into a life sentence.

But we did not do this constitutionally: the rules regarding registration of sex offenders are all statutes.

Does anyone truly benefit from putting this in Louisiana’s constitution?

Amendment 2: “Do you support an amendment to require a unanimous jury verdict in all noncapital felony cases for offenses that are committed on or after January 1, 2019?”

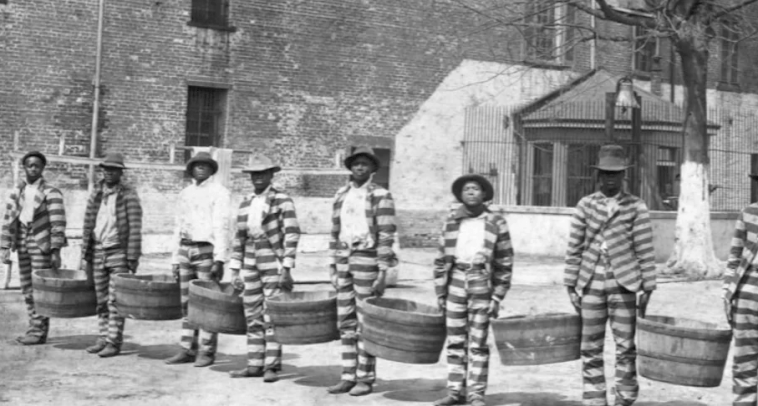

While the U.S. Constitution does not specifically require a unanimous jury of twelve for criminal convictions, the traditional practice and judicial precedent has long been that “due process of law”, with regard to liberty-depriving crimes includes proving “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the individual on trial did indeed commit the crime. From Louisiana’s admission into the union in 1812 until 1898, a unanimous jury was the law of this land.

But in the post-Reconstruction era, Louisiana’s 1898 Constitution changed that, permitting 9-3 verdicts for felony convictions. Ostensibly, this was to “relieve the parishes of the enormous burden of costs in criminal trials.” But the records of that constitutional convention show that its leader, E.B. Kruttschnitt, also stated that they were looking for “purification of the electorate” and the elimination of “the mass of corrupt and illiterate voters who have degraded our politics” – code words for white supremacy.

That provision was retained in the 1921 Louisiana constitution, then modified in the 1974 constitution, nudging the bar for conviction slightly upward to require a 10-2 conviction.

Does this change to unanimous juries belong in our state constitution now? Absolutely, for it returns and enacts the guarantees made at the beginning of that document, which states “All government, of right, originates with the people, is founded on their will alone, and is instituted to protect the rights of the individual and for the good of the whole. Its only legitimate ends are to secure justice for all, preserve peace, protect the rights, and promote the happiness and general welfare of the people.”

Who benefits, if this change is made? We all do. As state Sen. Dan Claitor (R-Baton Rouge) asked rhetorically during the debate over the amendment, “Is 10 out of 12 good enough for your children? Is 10 out of 12 good enough for your wife? Is 10 out of 12 good enough for your neighbor?”

Is 10 out of 12 truly “beyond a reasonable doubt”? If you were on trial, would 10 out of 12 be “good enough” for you?

Amendment 3: “Do you support an amendment to permit, pursuant to written agreement, the donation of the use of public equipment and personnel by a political subdivision upon request to another political subdivision for an activity or function which the requesting political subdivision is authorized to exercise?”

Currently, Louisiana’s constitution prohibits governmental agencies from donating or loaning resources except in emergencies. State statute, however, allows the sharing of resources, as long as there’s a written cooperative endeavor agreement in place to protect against governmental agencies simply “giving away” the proceeds from their own taxpayers.

In other words, it’s an unnecessary constitutional change.

Amendment 4: “Do you support an amendment to remove authority to appropriate or dedicate monies in the Transportation Trust Fund to state police for traffic control purposes?”

The Transportation Trust Fund, enacted as a constitutional amendment in 1990, dedicates the proceeds of the state fuel tax to road, bridge, port, airport and flood control construction and maintenance. But it also included the phrase “state police for traffic control purposes”. And while there are instances of legitimate use of a small portion of TTF for state police traffic control purposes – such as instituting contraflow for hurricane evacuations – is appropriate and necessary on occasion, previous administrations tapped TTF as general purpose funding for state police, under the guise of “traffic control.”

While the lawmakers passed a law in 2015, limiting any use of TTF funds for state police to $10-million per year, to take them completely out of the fund does require amending the constitutional amendment that created the Transportation Trust Fund in the first place.

In view of the $14-billion backlog of heretofore unfunded transportation construction needs in Louisiana, this amendment helps restore some of the public “trust” that the Transportation Trust Fund will be used for infrastructure. And considering that TTF is a finite resource, based on a per-gallon fuel tax. Its buying power dwindles each year, due in part to inflationary costs for construction, but also due to manufacturer and consumer moves toward more fuel-efficient vehicles and alternative fuel sources to power those vehicles. Additionally, incidents such as the Sunshine Bridge support being damaged by a barge require emergency spending on repairs, shifting millions from other scheduled projects and therefore adding to the backlog.

Opponents of the amendment, primarily ultra-conservatives, argue that Louisiana needs to remove restrictions on spending state tax dollars, rather than enhancing them. Some also suggest this is merely another step toward raising the fuel tax – a public relations move to make people more receptive to that idea.

Who benefits if this amendment passes? Not state police, certainly. But ensuring that fuel tax dollars are used for transportation construction and repairs could help reduce the wear and tear on your vehicle, insurance costs, and enhance commerce, as well as the economy.

Amendment 5: “Do you support an amendment to extend eligibility for the following special property tax treatments to property in trust: the special assessment level for property tax valuation, the property tax exemption for property of a disabled veteran, and the property tax exemption for the surviving spouse of a person who died while performing their duties as a first responder, active duty member of the military, or law enforcement or fire protection officer?”

Louisiana’s homestead exemption is one the state’s most notable “sacred cows.” It exempts homeowners from paying any property taxes on the first $75,000 value of their primary residence. Voters have granted additional property tax breaks to certain classes of people, including the elderly, disabled veterans, and surviving spouses of military members killed in action. This change would allow those qualifying for the enhanced property tax breaks to keep them, even after putting their primary residence in trust, which confers other tax benefits.

While the state constitution does not expressly prohibit levying a state property tax, Louisiana has not done so, leaving property taxes as the domain of parish and other local governing agencies. Each state-granted exemption from property tax (referred to as “ad valorem taxes” in the state constitution) then reduces the funds available for local government to provide services.

Where do we draw the line on tax exemptions for special interests?

Amendment 6: “Do you support an amendment that will require that any reappraisal of the value of residential property by more than 50%, resulting in a corresponding increase in property taxes, be phased-in over the course of four years during which time no additional reappraisal can occur and that the decrease in the total ad valorem tax collected as a result of the phase-in of assessed valuation be absorbed by the taxing authority and not allocated to the other taxpayers?”

Let’s say your home was valued at $150,000 four years ago, and now it’s assessed at $225,000. This amendment would let pay property taxes on a value of $167,000 this year, $184,000 next year, $201,000 the year after that, and on $225,000 in the fourth year – just in time for the next quadrennial reassessment.

But what if your $150,000 home was now valued at $220,000, or $210,000? You’d be paying 47% more, or 40% more in property taxes for the entire time.

This amendment, if passed, effectively contradicts the third enumerated right at the beginning of our state constitution, to wit: “No person shall be denied the equal protection of the laws.”

In addition to the underlying question of fairness, there’s a problem with the ballot language. It does not match the actual content of the legislation. The House amended this constitutional amendment, which started as Senate Bill 164, to make it only applicable to properties that qualify for the homestead exemption. They also made the tax collector (the sheriff) responsible for the phase in, not the assessor. But the House did not change the original ballot language to match.

Bottom line? This amendment, even if approved by voters, is very likely to have its constitutionality challenged in court.

The Bayou Brief’s recommendation, however, is simple. Rights, like the muscles of your body, atrophy when they’re not used. So exercise your rights, and vote.