For the past seven years, a David & Goliath struggle has taken place in Shreveport over the proposal to build a 3.6-mile long inner city connector (ICC) for Interstate 49 North. Building a short segment of highway does not seem like an issue that would generate much interest, let alone a fierce debate, but both sides—those for its construction and those against it—see the I-49 ICC having long-term ramifications for Shreveport as a city.

On the pro-I-49 ICC side, Shreveport’s city leaders and business community believe that bridging the almost four-mile gap in I-49 will jumpstart Shreveport’s economy, which never fully recovered from the oil and gas bust in the 1980s. On the anti-I-49 ICC side, the residents of the low-income, mostly black Allendale neighborhood, which four of the five proposed ICC routes would cut through, vehemently oppose it. They and other community activists think it will not only decimate the neighborhood and community, but will adversely affect Shreveport as a whole for years to come.

I-49 North’s construction was halted in the mid-1990s either because the city and state ran out of funds or because that segment of highway would have gone across environmentally protected wetlands—or likely both. The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was enacted in 1970. Entities proposing interstate highways have to submit an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), which then determines whether or not the proposed interstate route will adversely affect environmentally protected areas. If it does, FHWA will not approve the proposal.

The Northwest Louisiana Council of Governments (NLCOG), the transportation arm of the Shreveport Metropolitan Planning Commission (MPC) began the I-49 ICC Project in 2005. It did not complete the Project’s first stage (Stage 0 – Feasibility Study and Environmental Inventory) until May 2010. When NLCOG announced it would study the economic and environmental impact of four routes that cut through Allendale, all 3 to 4 miles long, residents of Allendale and others opposing NLCOG’s plan formed the group Loop It I-49. “Loop It” referred to their position of keeping I-49 North “looped” using Hwy. 3132. The much larger group advocating for having a through-Allendale route was first called “Thru the Heart I-49” and changed it later to “Thru the City I-49” after Loop It members pointed out that I-49 would cause the city to die if it went through the city’s heart.

Allendale residents who formed Loop It, now called #AllendaleStrong, obviously did so to save their houses from being demolished. But they and others in the area joined Loop It because they foresaw negative consequences for Shreveport and the region as a whole. John Perkins, who has become an expert on the history of inner city highways and their costly impact on cities, said the 3.6-mile I-49 ICC would destroy the Allendale community and cause Shreveport to sprawl out further. “No one wants to live or work in places right next to a highway,” he said. “You don’t want the air or noise pollution. Your quality of life will go down. So, people move out of the area and few people move in, so then you have abandoned houses. The only people who will go into an area like that are criminals and drug traders.” That pushes people and businesses in nearby neighborhoods out, too.” The result is people living farther away from the inner city areas in suburbs.

John Perkins, an #AllendaleStrong representative

Perkins points out that while residents who are forced to move out because of eminent domain will receive the “fair market value” for their property, once there is even a plan in place to build a highway, those residents are going to see their property values drop. “People who want the I-49 connector aren’t the ones who are going to lose their houses. They say, ‘Well, the Allendale people are going to be able to move to better neighborhoods and afford better houses because they’ll be compensated.’ But the value of their house will go down and they’ll receive less money than they would have if no highway had been proposed. They won’t be able to afford a better house and in fact, they may end up with a worse place.”

Highways can also produce a “border vacuum,” a barrier that discourages or even prevents people from crossing it, either on foot or in vehicles, to get from one area to another. (Few people will try to cross an interstate highway and not many like walking under them either.) This effect is also why urban areas and neighborhoods near highways often go decline economically.

The degradation if not ruin of Allendale would be especially tragic because the neighborhood has undergone a partial revitalization over the past ten years. Until 2005, Allendale seemed caught in an endless cycle of poverty, crime, and urban blight. It had been vibrant and economically stable through the 1960s, where the mostly African American residents formed a tight community. Then in the 1970s, Allendale began to decline, first from people moving out of the neighborhood and then because of the oil industry’s bust. Between 1970 and 2000, Allendale lost two-thirds of its population, according to the US Census Bureau. Many of the people who moved out of Allendale abandoned their houses and places of business, which then became havens for criminal activity — illegal drug trade and use, prostitution, and gang violence. By the mid-2000s, much of its property was adjudicated and most of the city saw Allendale as a lost cause.

In 2005, ironically, at the same time the I-49 ICC Project was being launched, a confluence of events occurred that started to revive Allendale. Shreveport had an influx of Hurricane Katrina evacuees, many of whom desperately needed shelter. The Fuller Center for Housing, a missionary, nonprofit organization, was founded at that time and partnered with the Shreveport-based, missionary nonprofit, Community Renewal International (CRI). They shared the common goal of reversing the cycle of poverty and high crime found in urban neighborhoods. The two organizations decided to build houses for the Hurricane Katrina victims and then for other low-income, working individuals and families who would buy the houes with interest-free mortgages. They chose Allendale as the location in which to build them, in an attempt to halt the poverty and crime. Since 2005, the Fuller Center and CRI have built and sold 48 houses in Allendale and the crime rate has dropped 50 percent.

In addition to how the ICC would affect Allendale residents personally, evidence points to the ICC being an economic boondoggle instead of a benefit. The estimated cost of building the 3.6-mile long ICC is $500 million. The federal government will pay 80 percent for constructing a new federal highway and the state has to pay for the remaining 20 percent, in this case, $100 million. The state of Louisiana currently has a $304 million budget deficit and would be hard-pressed to pay its $100 million share of the tab. In addition, the I-49 ICC was ranked somewhere in the middle of a list of all highway projects needed to be done in Louisiana. Even if the FHWA had given the green light to an ICC route, getting the necessary state funds for it could have delayed construction for years. In the meantime, the City of Shreveport would also have to spend money on maintaining I-49, I-20 and the state highways it uses.

#AllendaleStrong is now trying to persuade the City of Shreveport to connect the ends of I-49 with a business boulevard, akin to the multi-use surface streets Milwaukee, San Francisco, and other cities have built to replace their urban highways. #AllendaleStrong estimates the cost of upgrading a part of Route 71—used already to get back on I-49 North now—so it becomes an attractive, business boulevard, would cost $60 million. Drivers would have to drive more slowly on it than on the Hwy 3132 loop around the city, which would make it more likely they would see places they would want to visit. In #AllendaleStrong members’ minds, that would reap more economic benefits for the city than a through-highway with one exit that had a gas station and fast food place. A business boulevard would also not entail the high maintenance costs of a highway.

The conviction of Shreveport’s pro-ICC side that having I-49 run through its center will produce an economic windfall for the city is at odds with the current trend of cities all over the United States and the world. They are either dismantling their urban highways or planning to because their upkeep has become too expensive. In fact, cities that have taken down their inner city highways and replaced them with surface streets—San Francisco, Milwaukee, and Seoul, South Korea, for example—have seen their downtowns thrive. Perkins says cities using the “more permeable, multi-use routes such as boulevards and parkways” often revitalize neighborhoods along or near these types of roadways. Dallas, Houston, and New Orleans are all considering tearing down at least some of their inner city highways.

But the Shreveport groups who want the I-49 ICC look at the swirl of highways inside Dallas, the closest major city to Shreveport, and see it as a major reason for Dallas’ economic success. Their representatives have even suggested having inner city highways is a necessary stage for Shreveport to go through in order to have a strong economy (Shreveport is not bereft of inner city highways; Interstate 20 already goes through its downtown.) They believe a completed I-49 that goes through Shreveport’s center will attract businesses, not just gas stations and fast food restaurants along the highway, but ones that would move to Shreveport because it (finally) would have the “correct” infrastructure. NLCOG greatly bolstered their case by estimating the I-49 ICC’s annual economic impact would be $800 million, which anti-ICC people do not think is feasible. None of the people advocating for the I-49 ICC are also those who would lose their home or business or see their neighborhoods disrupted by the highway’s construction.

In September 2016, the MPC held a meeting, expecting the Baton Rouge-based Providence Engineering Group, whom NLCOG hired to conduct the I-49 ICC Project’s Phase 1 in-depth studies of the five possible ICC routes, to announce the two I-49 ICC routes it would recommend to FHWA. The federal agency would then determine if the routes complied with the NEPA. If one or both did, one would likely become the I-49 ICC.

The September 2016 meeting would have brought the project almost to the end of the second stage (the Planning and Environmental Stage). Since 2005, NLCOG has spent $3 million on the project, which the city paid for with Louisiana’s unclaimed property fund. The city and business leaders at the September meeting had become increasingly concerned by the project’s length, expense, and delays and were anxious to settle on a route. The Allendale residents and activists awaited Providence’s announcement with dread; they expected the selected routes would be two of the through-Allendale ones and knew they would have a tough fight to prevent its construction in the coming years.

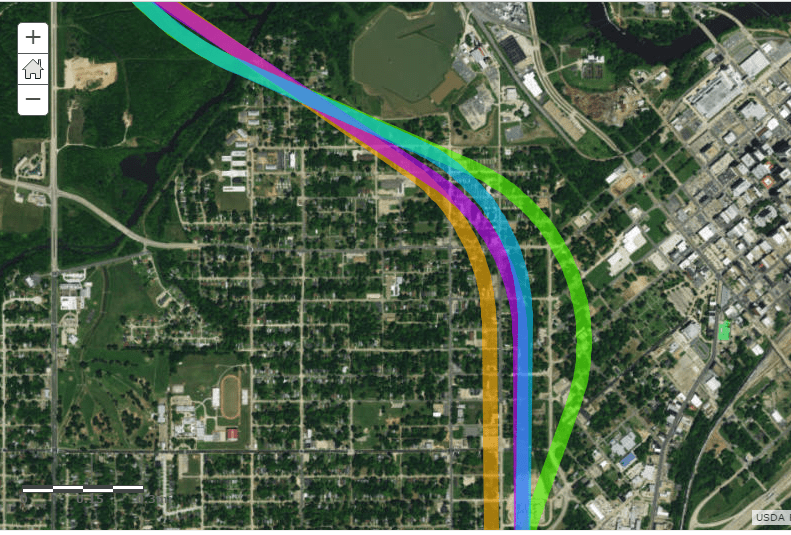

Four proposed ICC routes

Proposed routes with Hwy. 3132 in yellow

Instead, Providence stunned everyone at the meeting when a spokeswoman announced the group could not recommend any of the five I-49 ICC routes. During her Power Point presentation, she explained the reasons that none of the routes would pass FHWA regulations: All five routes had public structures or spaces, such as historical landmarks, parks and churches, which cannot legally be removed, harmed or destroyed in order to allow a federal highway to be built. One route would have cut through a historic landmark (Ledbetter Heights). Another had a Catholic church in its path, and its members declined the Shreveport Diocese’s offer to have it moved to a different area of the city.

A third option was the only route that did not cut through Allendale, keeping I-49 connected by the Hwy. 3132 loop. To become an official part of I-49, Hwy. 3132 would have to be upgraded to federal highway standards. However, that goes over Lake Cross, which is considered a public recreational area where people fish and swim.

The two through-Allendale center routes everyone at the meeting thought would be recommend for NEPA study have a public park in them, too (called SWEPCO Park since it is in sight of the electrical utility.) The members of the anti-I-49 ICC group, #AllendaleStrong, have learned since the September meeting that SWEPCO Park also contains the remains of one of four Civil War forts built in Shreveport, named for Confederate States General Albert Sidney Johnston. Once the fort is certified as a historic landmark, it would also prevent the ICC from being built through there. (The irony of a Confederate fort saving a black neighborhood from its decimation is not lost on the #AllendaleStrong members.)

Proponents of the I-49 ICC going through Allendale—mostly members of the highly respected business group, the Committee of One Hundred (C100)—expressed outrage at the September 2016 meeting. They denounced the “delay” in getting I-49 ICC routes approved by the FHWA. C100 member Patrick Harrison, who owns Sound Fighter Systems, (which conveniently manufactures sound panels for highways to muffle traffic noise) told the MPC, “I would strongly encourage you to do what you can to support Providence and…move it forward.”

While they understood that Providence’s inability to recommend any of the routes to the FHWA was a serious setback, C100 members did not seem to realize it was likely the death knell of the project. Given the money and time spent already on the project, they probably also decided the stakes had become too high to admit it was dead. David may have won that round, but Goliath was not going to give up.

At the meeting, Shreveport Mayor Ollie Tyler said she would work with Shreveport Parks and Recreation (SPAR) to find a way to get the I-49 ICC project back on track. John Perkins, who represented #AllendaleStrong at the meeting, interpreted her statement to mean she may try to de-commission SWEPCO Park. If she got its “city park” status removed, the routes that passed through it would then meet FHWA regulations, and the routes could be approved.

Perkins had already suspected the City was trying to de-commission SWEPCO Park. Seven months earlier, in February 2016, he and another opponent of I-49 ICC, Brian Salvatore, a chemistry professor at LSU-Shreveport, observed that SWEPCO’s playground equipment had disappeared. One day it was there; the next it wasn’t. Soon after, the barbecue implements went away. SPAR never made or posted an announcement at SWEPCO Park to warn they were removing the equipment. When Perkins asked SPAR why the equipment was removed, it said a lawsuit had been filed against them because the playground equipment was unsafe.

Perkins and others became more suspicious the City was trying to close down the park in October 2016. Allendale resident and #AllendaleStrong’s Vice President Louis Brossett noticed SPAR was not maintaining SWEPCO Park. The grass and weeds had grown thigh-high in areas, and snakes and even foxes were starting to make homes for themselves there. Brossett decided to mow the grass himself. When SPAR told him he could not do maintenance on the park because he was not an employee, Brossett and Perkins told media about the issue, and SPAR then sent an employee to cut the grass. The Shreveport Times reported SPAR Director Shelly Raigle defending the lack of attention to the park because “activity at the SWEPCO Park had greatly decreased,” families “utilize the seven other parks [that are] easily accessible,” and SPAR was limited in “the amount of resources” it could provide each park.

Allendale residents at SWEPCO Park

#AllendaleStrong Vice President Louis Brossett

In November 2016, Perkins, Brossett and #AllendaleStrong President Dorothy Wiley observed a SPAR employee starting to dismantle SWEPCO Park’s pavilion. As with the unmowed grass incident, SPAR denied they were doing so after a TV news crew arrived there. Raigle and Mayor Tyler’s spokeswoman Africa Price said there were no plans to take down the pavilion.

Dorothy Wiley, President of #AllendaleStrong

In early 2017, Perkins filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), requesting city government documents on SWEPCO Park. He obtained email correspondence among SPAR’s director, other SPAR employees and Mayor Tyler as well as among SPAR, Mayor Tyler and Providence Engineering. Dating back to at least April 2016, the emails show that the City was trying to close the park down for the purpose of getting an I-49 ICC route approved by the FHWA.

An April 2016 email from a SPAR employee said the SPAR Director wanted playground equipment, picnic tables, a walkway and the pavilion removed for “the demolition” of SWEPCO Park. Given that the playground equipment was removed in February 2016, Providence Engineering and the City had anticipated the through-Allendale routes would not pass FHWA regulations at least seven months before Providence’s announcement at the September 2016 meeting, and began taking steps to remove public spaces from the routes.

On April 20th, 2017, NLCOG held a public meeting, so Providence Engineering could give the first update on the I-49 ICC since announcing in September 2016 it couldn’t recommend any of the proposed routes. At the meeting, Providence declared it planned to complete the Environmental Impact phase of the project by further “studying” I-49 ICC Route 1, which has SWEPCO Park on it, in addition to Route 5, the upgraded Hwy. 3132 loop, which has Cross Lake below it. Specifically, Providence said it was examining the “significance” of SWEPCO Park and Cross Lake. “Significance” refers to one of the property criteria of public spaces or organizations in Section 4(f) of the U.S. Department of Transportation Act of 1966. If the FHWA determines the public space or organization meets all of the criteria, it will remove that proposed route from further consideration. The criteria are:

1. It must be publicly owned.

2. It must be open to the public.

3. Its major purpose must be for park, recreation, or refuge activities.

4. It must be significant as a park, recreation area, or refuge

Although the FHWA had already determined that the public spaces and organizations on all five proposed I-49 ICC routes fit all the property criteria in Section 4(f), Providence had clearly decided it would try to get the FHWA to change its ruling that SWEPCO Park constituted a “significant” property. Not by coincidence, Mayor Tyler finally openly announced that the city planned to close SWEPCO Park at that April 20 meeting.

The day after the meeting, the Louisiana Department of Transportation (LDOT), posted an update of the I-49 ICC project’s progress on its website. It summarized the reasons for closing SWEPCO Park:

The City of Shreveport has determined that SWEPCO Park is not significant and plans to close the park based on its assessment as unsafe, no equipment is on site, and the community is served by other multi-use parks managed by the City. (emphasis added)

Providence has requested the FHWA review and approve the City of Shreveport’s determination that SWEPCO Park and Cross Lake do not fit Section 4(f) because they are not significant.

John Perkins believes the City and Providence’s attempt to close down SWEPCO Park will fail. For one, FHWA’s ruling that the public spaces on all five proposed routes meet all 4(f) requirements has not changed over the past year. He pointed out that last year, SPAR deemed SWEPCO Park “underutilized”, but at the September 2016 meeting, Providence reported that the FHWA told them that even an underutilized park is still a park.

Perkins also said FHWA does not take kindly to any sign of an entity “gaming the system.” He cited a case in Bossier City, which is just a couple of miles across the Red River from Shreveport. When Bossier placed signs along their preferred route for a road overpass before a route was chosen, the Feds rejected the project altogether. But in case FHWA needs to be further persuaded the City is gaming the system, Perkins has sent the emails and news articles he received from his FOIA request.

It looks promising that the City will fail in its bid to have an I-49 ICC through Allendale. If Allendale wins, it will be because Shreveport’s business and city leaders did not think the rules applied to them and thought using heavy-handed tactics–such as removing playground equipment from a park or getting Catholic leaders to pressure a church to move—would get them what they wanted. The prevailing attitude was low-income African Americans should submit to wealthy, mostly white people’s demands. So this thinking goes, Allendale residents should lose their homes and community so that wealthier whites can save ten minutes on their commute time.

A final reason for Allendale winning the fight is the US Department of Transportation’s scrupulous adherence to their rules and procedures. The federal government gets a bad rap, which it deserves sometimes. In this case, it deserves high praise.